The Tragic Legacy of Andrés Escobar: Justice Delayed Three Decades Later

A Soccer Legend’s Senseless Death

The world of soccer was shaken once again this week with news from Colombia that brings closure to one of the sport’s most heartbreaking chapters. Santiago Gallon Henao, a drug trafficker long suspected of orchestrating the 1994 murder of beloved Colombian soccer player Andrés Escobar, has been killed in Mexico, according to Colombian President Gustavo Petro. The announcement came on Friday, nearly three decades after Escobar’s shocking assassination sent waves of grief throughout Colombia and the international soccer community. Escobar, who served as the Colombian national team’s central defender, was only 27 years old when his life was brutally cut short in a Medellín nightclub parking lot. His death wasn’t just the loss of a talented athlete—it became a symbol of the violence and chaos that gripped Colombia during one of the darkest periods in the nation’s history, when drug cartels held cities hostage and murder rates reached unprecedented levels.

The Fatal Own Goal That Changed Everything

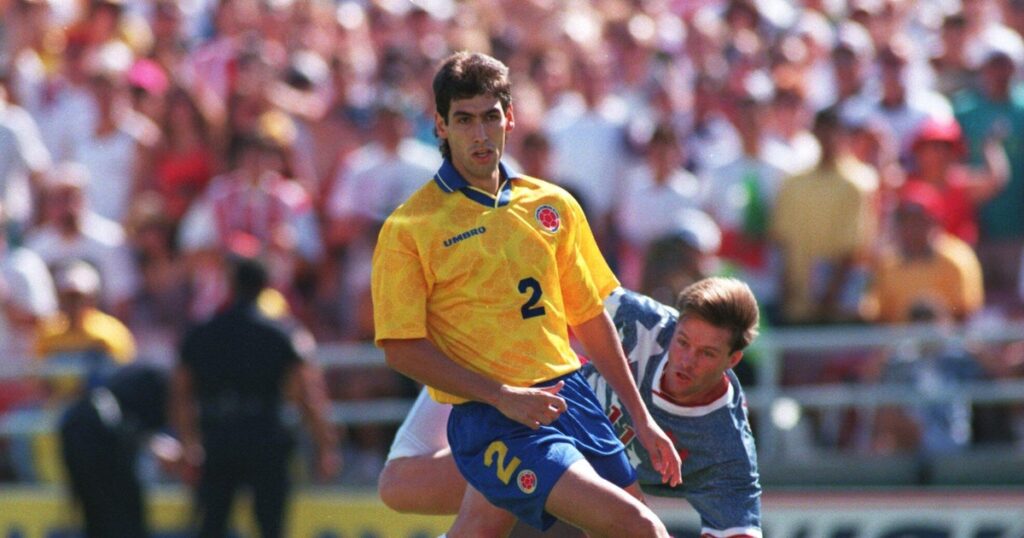

The tragedy that led to Andrés Escobar’s death began on a soccer field thousands of miles away in Los Angeles during the 1994 FIFA World Cup. On June 22, Colombia faced the United States in a first-round match that would prove fateful. During the game, Escobar accidentally scored an own goal while attempting to defend against a shot from U.S. forward John Harkes. The unfortunate error contributed significantly to Colombia’s elimination from the tournament during the first round—a devastating outcome for a team that had entered the competition with high expectations. Colombia had been considered one of the favorites to win the World Cup that year, and their early exit was seen as a national humiliation. For Escobar, a dedicated professional known for his skill and sportsmanship, the own goal was simply a mistake—the kind that can happen to any player in the heat of competition. However, in the volatile atmosphere of 1994 Colombia, where drug traffickers had placed enormous bets on the national team’s success, this simple mistake would have deadly consequences that no one could have imagined.

A Nightclub Confrontation Turned Fatal

Just ten days after that fateful World Cup match, on July 2, 1994, Andrés Escobar’s life came to a violent end. According to investigations, Santiago Gallon Henao and his brother confronted the soccer star at a nightclub in Medellín, a city then firmly under the control of drug trafficking organizations. At that time, Medellín was experiencing a staggering murder rate of 380 per 100,000 inhabitants, making it one of the most dangerous cities in the world. The Gallon brothers, believed to have lost heavily on bets placed on Colombia’s World Cup performance, allegedly orchestrated what happened next. Their driver, Humberto Munoz Castro, followed Escobar to the nightclub’s parking lot and shot him multiple times. Eyewitnesses to the horrific scene reported that Munoz shouted “goal!” with each shot he fired—a cruel mockery of the own goal that had sealed Colombia’s fate in the tournament. Munoz later confessed to pulling the trigger and was sentenced to 43 years in prison, though he was released after serving only 11 years, according to reports from the Bogota Post. The murder shocked not just Colombia but the entire world, highlighting the dangerous intersection of sports, gambling, and organized crime.

The Long Shadow of Impunity and Investigation

While Humberto Munoz Castro admitted to being the gunman, the Gallon brothers faced a different legal journey. Santiago Gallon Henao and his brother were investigated for obstruction of justice in connection with Escobar’s murder and spent 15 months in prison. However, they were never formally brought to trial for their alleged role in orchestrating the assassination. This lack of prosecution became another painful reminder to Colombians of how powerful criminals could often evade full accountability for their actions during that turbulent era. The brothers’ connections to organized crime ran deep—in 2015, both were included on a U.S. Treasury Department blacklist for drug trafficking. They were accused of being members of La Oficina de Envigado, an organization that emerged as a successor to the infamous Medellín Cartel once led by drug kingpin Pablo Escobar (no relation to Andrés). The parallels between the two Escobars—one a gentle defender on the soccer field, the other a ruthless criminal empire builder—were explored in the acclaimed 2010 ESPN documentary “The Two Escobars,” which examined how their lives, though vastly different, became intertwined in Colombia’s narrative of violence and redemption.

Justice Delivered in an Unexpected Place

President Gustavo Petro’s announcement that Santiago Gallon Henao had been killed Thursday in Mexico brought unexpected news of a sort of street justice, though not the legal accountability many had hoped for. According to a source from the Toluca prosecutor’s office who spoke with AFP, Gallon was shot dead in a restaurant in Huixquilucan, a municipality in the state of Mexico, just outside Mexico City. The circumstances of his death remain under investigation by Mexican authorities. President Petro, Colombia’s leftist leader, used the platform X (formerly Twitter) to confirm Gallon’s death and to state definitively that he was responsible for Andrés Escobar’s killing. Petro emphasized that the soccer star’s murder had “destroyed the country’s international image” at a time when Colombia was already struggling with its reputation due to drug violence and cartel warfare. While Gallon’s death brings a certain closure, it also serves as a reminder that he never faced trial for his alleged role in ordering one of Colombia’s most notorious murders—a fact that continues to highlight the challenges Colombia faced in administering justice during the cartel era.

Remembering Andrés Escobar’s True Legacy

Nearly thirty years after his death, Andrés Escobar remains a beloved figure in Colombian sports history, remembered not for a single tragic mistake on the field but for his character, skill, and the grace with which he played the game. After the own goal but before his murder, Escobar wrote a column for El Tiempo newspaper in which he reflected on the loss and looked forward to the future, ending with the poignant words: “Life doesn’t end here.” Those words have taken on profound meaning for Colombians who have worked to ensure that his memory represents something greater than the violence that took his life. Fans continue to honor him at matches, displaying banners with his image and name, as they did during the 1998 World Cup match between Colombia and Tunisia in Montpellier, France. His story has been told and retold through documentaries, articles, and books, serving as both a cautionary tale about the dangers of mixing sports with organized crime and a reminder of an innocent life lost to senseless violence. Colombia has changed dramatically since 1994—murder rates have dropped significantly, the major cartels have been dismantled, and the country has worked to rebuild its international reputation. Yet the memory of Andrés Escobar endures as a symbol of a painful past and a reminder of the human cost of violence. His legacy lives on not in the own goal that contributed to his death, but in the dignity, passion, and love for soccer that defined his all-too-short life.