The Extended Space Mission: What Nearly Nine Months in Orbit Means for Stranded Astronauts

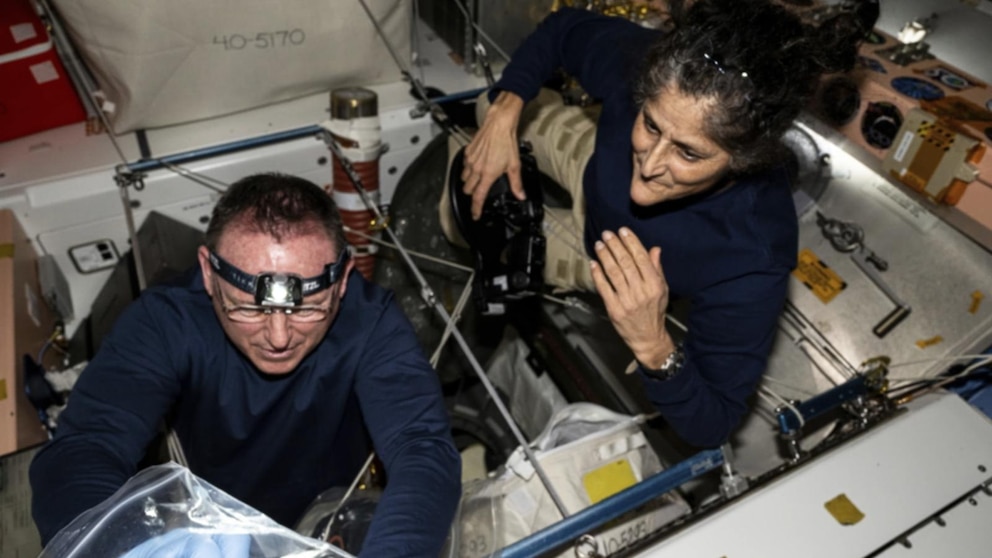

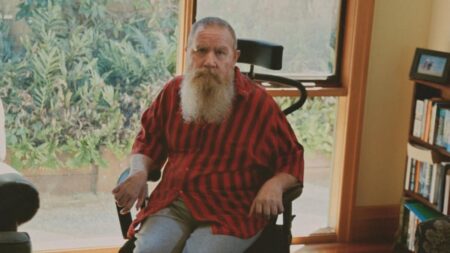

When NASA astronauts Barry “Butch” Wilmore and Sunita “Suni” Williams launched into space aboard Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft, they expected a routine eight-day mission to the International Space Station. Instead, technical malfunctions with their return vehicle have transformed their brief visit into an unprecedented nine-month ordeal in orbit. As their extended stay continues to make headlines, experts are raising important questions about what this prolonged exposure to the space environment might mean for their physical and mental health. ABC News recently consulted with astrophysicist Hakeem Oluseyi to better understand the biological challenges these experienced astronauts are facing and what awaits them when they finally return to Earth.

The human body is remarkably adaptable, but it evolved over millions of years to function in Earth’s gravitational environment. When astronauts venture into the microgravity of space, virtually every system in their bodies must adjust to conditions that are fundamentally alien to our biology. What makes the situation of Wilmore and Williams particularly noteworthy isn’t just the duration of their unplanned stay, but the fact that they had mentally and physically prepared for just over a week in space, not the better part of a year. This psychological element adds another layer of complexity to an already challenging situation, as the astronauts have had to recalibrate their expectations while simultaneously dealing with the physical demands of long-duration spaceflight.

How Microgravity Transforms the Human Body

The most immediate and perhaps most significant change astronauts experience in space involves their musculoskeletal system. On Earth, our bones and muscles are constantly working against gravity—even something as simple as standing requires muscular effort and places stress on our skeletal structure that helps maintain bone density. In the weightless environment of the International Space Station, this constant resistance disappears. As astrophysicist Hakeem Oluseyi explained to ABC News, without the mechanical stress that gravity provides, astronauts begin losing bone density at an alarming rate—approximately 1-2% per month in weight-bearing bones like those in the hips, spine, and legs. Over the course of nine months, Wilmore and Williams could potentially lose between 9-18% of their bone mass in these critical areas, comparable to what an elderly person with osteoporosis might experience over several years.

Muscle atrophy presents an equally serious concern. Without gravity requiring them to support their own body weight, astronauts’ muscles—particularly those in the legs, back, and core that we use constantly on Earth—begin to waste away. Despite rigorous daily exercise regimens that can include up to two hours of resistance training and cardiovascular work on specialized equipment, astronauts still experience significant muscle loss. The longer Wilmore and Williams remain in space, the more pronounced this deterioration becomes. This isn’t merely an aesthetic issue; muscle mass is crucial for metabolic health, mobility, and the ability to perform even basic tasks. The cardiovascular system also adapts to microgravity in ways that can be problematic upon return to Earth. In space, the heart doesn’t have to work as hard to pump blood throughout the body because gravity isn’t pulling fluids downward. This can lead to cardiac deconditioning, where the heart muscle itself may become slightly weaker. Additionally, blood volume decreases in space, and the distribution of fluids shifts toward the upper body and head, causing that characteristic puffy-faced appearance many astronauts develop in orbit.

Vision, Radiation, and Other Hidden Health Risks

Beyond the more visible changes to bone and muscle, astronauts on extended missions face several less obvious but equally concerning health challenges. One of the most puzzling and troubling is a condition known as spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS). Many astronauts who spend extended periods in space experience changes to their vision, sometimes permanently. The fluid shift toward the head that occurs in microgravity can increase pressure within the skull, potentially flattening the back of the eyeball, causing the optic nerve to swell, and even creating folds in the choroid, the vascular layer of the eye. Some astronauts have returned from long-duration missions with lasting vision impairment, requiring them to use glasses when they didn’t need them before spaceflight. The exact mechanisms aren’t fully understood, and researchers are still working to develop effective countermeasures. For Wilmore and Williams, their extended mission increases their exposure to whatever factors contribute to this condition.

Radiation exposure represents another serious concern for astronauts beyond Earth’s protective magnetic field and atmosphere. The International Space Station orbits within Earth’s magnetosphere, which provides some protection, but astronauts still receive radiation doses far exceeding what people on Earth experience. This radiation comes from galactic cosmic rays—high-energy particles from outside our solar system—and from solar particle events when the sun releases bursts of radiation. Over nine months, the cumulative radiation dose increases the astronauts’ lifetime risk of developing cancer and may also contribute to other health issues, including potential impacts on the central nervous system. NASA carefully monitors radiation exposure and has lifetime limits for astronauts, but an unexpectedly extended mission like this one wasn’t part of the original risk calculation for Wilmore and Williams. Their bodies are essentially serving as test cases for understanding human resilience in the space environment over timescales they hadn’t anticipated.

The Psychological Dimension of an Unplanned Extended Mission

While the physical challenges of long-duration spaceflight are significant and well-documented, the psychological aspects of Wilmore and Williams’s situation deserve equal attention. These are highly trained, experienced astronauts—Williams has actually spent more cumulative time in space than any other female astronaut—so they possess the mental fortitude and coping skills necessary for the demands of spaceflight. However, there’s a profound difference between mentally preparing for a week-long mission and suddenly facing nine months away from Earth. The psychological impact of this dramatic extension, combined with the knowledge that technical failures stranded them there, adds stress that even the most rigorous astronaut training cannot fully prepare someone for.

Isolation and confinement in the space station environment can take a toll on mental health over extended periods. While the ISS is relatively spacious as spacecraft go, it’s still a confined environment shared with a small crew, operating on a rigid schedule, with limited privacy and no opportunity to step outside for fresh air or a change of scenery. Astronauts are separated from family and friends, missing important life events and milestones back home. Communication with Earth, while regular, involves time delays and is mediated through technology. The absence of natural light cycles, familiar foods, and other comforts of home can contribute to feelings of isolation. Moreover, knowing that their return has been delayed due to spacecraft issues—factors outside their control—could contribute to feelings of frustration or helplessness. NASA’s psychological support systems include regular contact with flight surgeons and psychologists, private family conferences, and care packages from Earth, but these can only partially compensate for the unexpected extension of their mission.

The Road to Recovery: Returning to Earth After Extended Spaceflight

When Wilmore and Williams finally return to Earth, their challenges will be far from over. The transition from microgravity back to Earth’s gravitational field is extremely difficult for astronauts after long-duration missions, and the longer they’ve been in space, the harder the adjustment typically becomes. Upon landing, they will likely need assistance even standing up and walking, as their bodies will have partially forgotten how to balance and coordinate movements against gravity. The sensation of weight—feeling the pull of gravity on their bodies again—can be overwhelming and exhausting. Simple activities that we take for granted, like sitting upright without support or lifting objects, may initially be challenging because their muscles have weakened considerably.

The rehabilitation process following a long space mission is extensive and carefully monitored. Wilmore and Williams can expect to undergo comprehensive medical evaluations, followed by structured physical therapy and reconditioning programs that will gradually rebuild their bone density and muscle strength. Recovery timelines vary by individual, but astronauts typically need several months to regain their pre-flight physical condition, with bone density taking the longest to recover—sometimes a year or more. Their cardiovascular systems will need time to readjust to pumping blood against gravity again. They may experience orthostatic intolerance, where standing up quickly causes dizziness or fainting because their bodies have lost some ability to regulate blood pressure in response to postural changes. Their balance and spatial orientation may also be temporarily impaired as their vestibular systems—the inner ear mechanisms that help us maintain balance—recalibrate to Earth’s environment. Throughout this recovery period, NASA’s medical teams will monitor them closely, tracking biomarkers, conducting scans to assess bone and muscle recovery, and watching for any unexpected complications that might emerge from their extended time in space.

What This Mission Teaches Us About the Future of Space Exploration

The unplanned extended mission of Wilmore and Williams, while unfortunate from their personal perspective, provides NASA and the broader space science community with valuable data about human resilience and adaptation during long-duration spaceflight. As humanity sets its sights on more ambitious goals—returning to the Moon with the Artemis program and eventually sending humans to Mars—understanding how the human body responds to extended periods in space becomes increasingly critical. A round-trip mission to Mars, for example, could take two to three years with current propulsion technology, making the nine-month experience of these astronauts a modest preview of what future deep-space explorers will face.

This situation has also highlighted the importance of reliable spacecraft systems and the need for redundancy in human spaceflight programs. The technical issues that prevented Wilmore and Williams from returning on their original spacecraft underscore how much we still have to learn about safely transporting humans to and from space. It has reinforced NASA’s commitment to having multiple commercial partners for crew transportation, ensuring that if one system fails, alternatives exist. Looking forward, the lessons learned from keeping these astronauts healthy and functional during their extended stay will inform the development of better countermeasures—improved exercise equipment, pharmaceutical interventions, nutritional strategies, and perhaps even artificial gravity systems—that could protect future astronauts on journeys that venture farther from Earth than ever before. Wilmore and Williams, though inadvertent participants in this extended mission, are contributing to our understanding of human spaceflight in ways that will benefit the astronauts who follow in their footsteps, whether to lunar bases, Mars expeditions, or destinations we haven’t yet imagined.