The Rise of DIY Biohackers: When Humans and Machines Become One

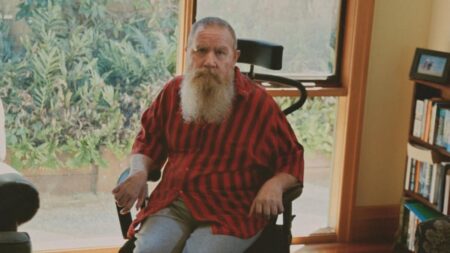

In a world where science fiction increasingly becomes reality, a growing community of self-described biohackers is pushing the boundaries of what it means to be human. These aren’t characters from a dystopian novel or high-budget film – they’re real people gathering at events like Grindfest, an annual convention that has become ground zero for those seeking to merge their bodies with technology. ABC News reporter Nathan Rousseau Smith recently ventured to the tropical island of Roatán to witness this extraordinary movement firsthand, where enthusiasts willingly undergo procedures to implant microchips and other technological devices beneath their skin. What drives someone to voluntarily become part-machine? The answers reveal a fascinating subculture that exists at the intersection of technology, philosophy, and human enhancement, operating in regulatory gray zones where traditional medical oversight gives way to personal experimentation and collective exploration.

The biohacking movement represents a fundamental shift in how some people think about the human body and its limitations. For these pioneers, the flesh-and-blood body we’re born with isn’t a sacred vessel to be preserved in its original state, but rather a platform for continuous improvement and customization. At Grindfest and similar gatherings, participants don’t just theorize about human enhancement – they actively practice it. The event draws biohackers from around the world who share a common vision: a future where the line between human and machine becomes increasingly blurred, where technology isn’t something we carry in our pockets but something integrated into our very being. These aren’t wealthy tech executives with access to cutting-edge medical facilities; rather, they’re everyday people – programmers, artists, students, and professionals from various backgrounds – united by their belief that humanity’s next evolutionary step won’t be biological but technological. They see themselves as explorers charting unknown territory, voluntarily becoming test subjects in experiments that could eventually benefit all of humanity, or at least those willing to follow their cybernetic path.

The choice of Roatán as the gathering place for Grindfest is no accident. This small island off the coast of Honduras offers something increasingly rare in our heavily regulated world: relative freedom from the strict medical regulations that govern body modification procedures in countries like the United States and throughout Europe. While Western nations have developed extensive legal frameworks around medical procedures, implantable devices, and who can perform various interventions on the human body, Roatán represents a frontier where biohackers can pursue their visions with fewer legal obstacles. This doesn’t mean the environment is lawless or reckless; rather, it provides a space where individuals can exercise greater autonomy over their own bodies without navigating bureaucratic hurdles. For biohacking enthusiasts, this regulatory flexibility is essential. They argue that mainstream medical systems move too slowly, bound by excessive caution and institutional inertia that prevents innovation. Traditional clinical trials and approval processes can take years or even decades, during which time technology advances at breakneck speed. By operating in more permissive jurisdictions, biohackers can experiment with new implants, test novel applications, and push boundaries that would be impossible in more restrictive environments. Critics might call it dangerous; participants call it necessary for progress.

The actual procedures performed at events like Grindfest range from relatively simple to surprisingly complex. The most common intervention involves implanting RFID (Radio-Frequency Identification) chips beneath the skin, typically in the webbing between the thumb and forefinger. These tiny devices, no larger than a grain of rice, can be programmed to perform various functions: unlocking doors, starting cars, storing medical information, or sharing contact details with a simple hand gesture. The implantation process itself is quick – lasting just minutes – and resembles getting a piercing more than traditional surgery. More advanced biohackers go further, experimenting with magnets that allow them to sense electromagnetic fields, LED lights visible beneath the skin, or even devices that can monitor internal body conditions and transmit data to external devices. Some participants have developed implants that can store and transfer cryptocurrency, turning their bodies into walking digital wallets. Others are working on sensory augmentation – implants that could theoretically allow humans to perceive wavelengths of light normally invisible to us, or detect magnetic fields like migratory birds. The philosophy underlying these modifications goes beyond mere convenience or novelty. For true believers, each implant represents a step toward transcending biological limitations that have constrained humanity since our species emerged.

The biohacking community faces significant criticism from medical professionals, ethicists, and regulators who worry about both individual safety and broader social implications. Medical experts point out the very real risks involved in implanting foreign objects into the body without proper sterile environments, trained surgeons, or emergency medical backup. Infections, rejection by the immune system, device migration, and tissue damage are all potential complications. There’s also concern about long-term effects that won’t be apparent for years or decades – what happens when these implanted devices fail, become obsolete, or need to be removed? Beyond physical safety, critics raise questions about data security and privacy. If your body contains chips that store personal information or interact with external systems, what happens when those systems are hacked? Could biometric implants make identity theft more consequential, or create new vulnerabilities to surveillance? Ethicists also wonder about social equity – if body modification technology advances and becomes desirable for employment or social participation, could we create a two-tiered society of the enhanced and the unmodified? Others worry about psychological effects, particularly body dysmorphia or addiction to modification, and the potential for coercion in contexts where enhanced capabilities provide competitive advantages.

Despite these concerns, the biohacking movement continues to grow, driven by a potent combination of technological enthusiasm, libertarian philosophy, and genuine curiosity about human potential. For participants, the criticism often misses the point. They argue that humans have always modified their bodies and extended their capabilities through technology – from eyeglasses to pacemakers, from hearing aids to artificial joints. Biohackers see themselves as simply taking the next logical step in this ongoing process. They emphasize personal autonomy and the right to make decisions about their own bodies, particularly when it comes to enhancement rather than medical necessity. Many are well-educated about the risks they’re taking and accept them as the price of pioneering new frontiers. The community has also developed its own safety culture, with experienced practitioners mentoring newcomers, sharing best practices for sterile procedures, and documenting their experiences online to help others learn from both successes and failures. Looking forward, whether this movement represents the vanguard of humanity’s inevitable merger with machines or a cautionary tale about the dangers of unregulated self-experimentation remains to be seen. What’s certain is that as technology continues advancing and becoming more miniaturized, affordable, and capable, the questions raised by biohackers will only become more pressing for society at large. The future they’re building in their own bodies – on regulation-friendly islands and in underground communities worldwide – may eventually arrive for everyone, forcing us all to consider what it means to be human in an age where biology and technology increasingly intertwine.