The Case of Charles “Sonny” Burton: A Death Penalty Dilemma

A Man Facing Death for a Crime He Didn’t Commit

Charles “Sonny” Burton’s case represents one of the most troubling contradictions in America’s justice system. At 75 years old, this frail man who now requires a wheelchair to move around could become one of the rare individuals executed in the United States despite never having pulled a trigger or taken a life. His story centers on a 1991 robbery at an AutoZone store in Talladega, Alabama, where customer Doug Battle was shot and killed. While no one disputes that it was Derrick DeBruce who fired the fatal shot—not Burton—Alabama is preparing to execute Burton using nitrogen gas. What makes this case particularly heartbreaking is that DeBruce himself, the actual shooter, had his death sentence reduced to life imprisonment years ago, leaving Burton as the only person still facing execution for this crime. Burton was outside the store when the shooting occurred, yet he sits on death row while the man who actually killed Battle will live out his days in prison. This glaring disparity has created a groundswell of support for clemency, including from unexpected voices: the victim’s own daughter and several of the jurors who originally sentenced Burton to death.

The Crime and Its Circumstances

On August 16, 1991, six men participated in a robbery at an AutoZone auto parts store. Burton, then 40 years old, was among them and admittedly played a role in the crime. Before entering the store, he allegedly said that if anyone caused trouble, he would “take care of it”—a statement that prosecutors would later use to paint him as the robbery’s ringleader. Armed with a gun, Burton forced the store manager to the back to open the safe while DeBruce ordered everyone else to get down. As the robbery was concluding and the men were leaving, Doug Battle, a 34-year-old Army veteran and father of four, entered the store. He immediately complied with the robbers’ demands, throwing down his wallet and getting on the floor. According to testimony from LaJuan McCants, who was only 16 at the time, Burton and the others had already left the store when DeBruce shot Battle in the back. In the getaway car afterward, Burton reportedly asked DeBruce why he had shot the man—a question that suggests Burton himself was surprised by the violence. During the trial, prosecutors argued that Burton was “just as guilty as Derrick DeBruce, because he’s there to aid and assist him,” using that pre-robbery statement as evidence of Burton’s leadership role and intent. Burton’s defense attorneys countered that while their client clearly intended to participate in a robbery, there was no evidence he intended for anyone to be harmed or killed.

A Jury’s Regret and the Victim’s Daughter’s Plea

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of Burton’s clemency petition comes from those who helped put him on death row in the first place. Six of the eight living jurors from his 1992 trial now say they do not object to his sentence being commuted, with three actively requesting clemency from Governor Kay Ivey. These jurors say they never would have recommended death if they had known the actual shooter would receive a lesser sentence. Priscilla Townsend, one of these jurors, has become particularly vocal about her regret. In a telephone interview, she stated plainly: “It’s absolutely not fair. You don’t execute someone who did not pull the trigger.” She explained that the jury recommended death after an extremely emotional trial, but that decades of reflection have changed her perspective. While she still believes in capital punishment “for the worst of the worst,” she no longer believes that description fits Burton. In a powerful essay published by AL.com titled “I sentenced a man to die in Alabama. I was wrong,” Townsend detailed how the prosecution’s portrayal of Burton as the “ring leader” shaped everything about how the jury viewed the case—the evidence, the assignment of responsibility, and the justification for punishment. She wrote that she believed this narrative at the time, but no longer does. Even more striking is the position taken by Tori Battle, who was just 9 years old when her father was murdered. In a letter to Governor Ivey, she asked the governor to “consider extending grace to Mr. Burton and granting him clemency,” noting that her father “was strong, but he valued peace. He did not believe in revenge.”

The Legal Framework and Its Controversies

Burton’s case exists within a complex and controversial legal framework. Twenty-seven states allow people to be executed for participating in a felony that resulted in someone’s death, even if they didn’t directly kill anyone—a legal doctrine known as “felony murder.” While most people on death row were convicted of directly killing someone, the U.S. Supreme Court allows the execution of accomplices under certain circumstances established in a 1987 ruling. According to that decision, accomplices who didn’t pull the trigger can be sentenced to death if they displayed “reckless indifference” for human life. The Death Penalty Information Center has documented at least 22 cases where the person executed participated in a felony during which a victim died at the hands of another participant, making Burton’s situation rare but not unprecedented. However, legal experts point out inconsistencies in how this standard is applied. Robin M. Maher, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, says this has created “arbitrariness among the jurisdictions.” Richard S. Jaffe, an attorney not involved with Burton’s case, noted that Alabama law requires prosecutors to show the accomplice had a “particularized intent to kill”—something Burton’s lawyers argue was never established in his case. Burton’s attorney, Matt Schulz, calls the case “an extreme outlier” among death penalty cases and argues it “slipped through the cracks” of the justice system. The Alabama Attorney General’s office, however, opposes clemency, pointing out that Burton was convicted of capital murder in 1992, the jury unanimously recommended death, and that conviction has been upheld at every level of appeal.

The Human Behind the Case

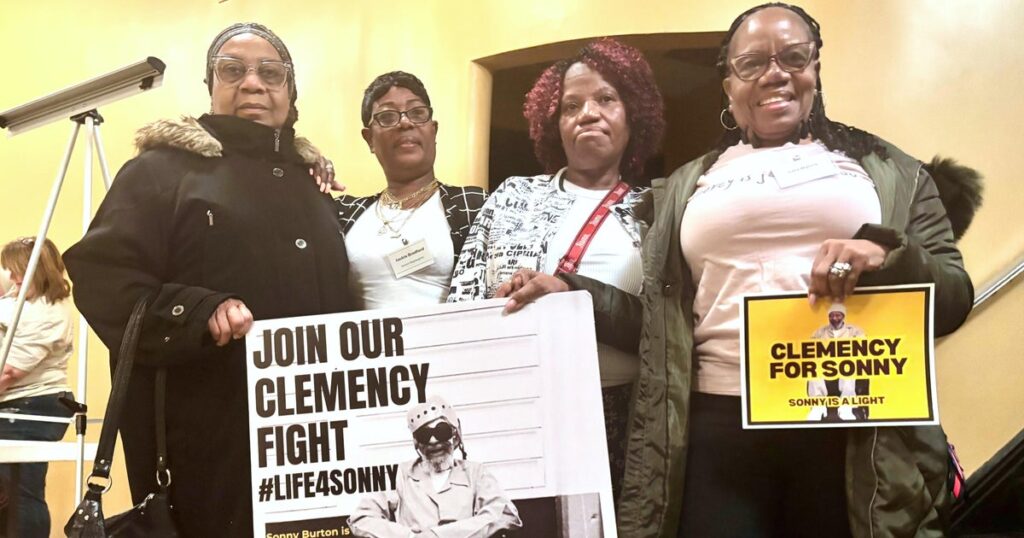

Beyond the legal arguments lies a human story. Burton grew up in difficult circumstances with an alcoholic father who frequently beat him, according to sentencing documents. Despite this traumatic childhood, his sister Eddie Mae Ellison remembers him as a protector for younger family members—someone who shielded others from harm despite suffering himself. Ellison insists her brother “is not perfect, but he is not the person depicted by prosecutors.” She describes visiting her now-75-year-old brother, whose health has deteriorated significantly during his decades on death row. He’s frail, using a wheelchair or walker to move around outside his cell—a far cry from the threatening “ringleader” prosecutors portrayed at trial. With anguish in her voice, Ellison asks a simple question that cuts to the heart of the matter: “He did not lay a hand on the man. Why do you feel it is necessary to take his life?” This question resonates with those calling for clemency, who see a fundamental injustice in executing someone who didn’t kill anyone while allowing the actual killer to live. The clemency supporters aren’t arguing that Burton is innocent of wrongdoing—he participated in an armed robbery, a serious violent crime. But they’re arguing that executing him while the shooter lives creates an indefensible contradiction in justice.

Questions of Justice and Mercy

Burton’s case forces us to confront difficult questions about justice, proportionality, and mercy in America’s criminal justice system. How can it be just to execute someone who didn’t kill anyone while the person who actually committed the murder serves a life sentence? What does it say about our system when the victim’s own daughter and the jurors who imposed the sentence now believe it’s wrong? Burton’s supporters, including his attorney Matt Schulz, emphasize that this isn’t the kind of case most people envision when they think about capital punishment. They argue that clemency grants, while rare, exist precisely for situations like this—when the machinery of justice produces an outcome that, upon reflection, seems fundamentally unfair. Governor Kay Ivey has granted clemency only once during her tenure, and clemency is exceedingly rare in death penalty cases across the country. However, there are precedents: Republican governors in several states have extended clemency for accomplices in murder cases, including Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt, who commuted a death sentence in November 2024. As the Alabama Supreme Court has authorized Governor Ivey to set an execution date using nitrogen gas—itself a controversial method—Burton’s fate now rests in her hands. The question before her is not whether Burton participated in a serious crime—he clearly did—but whether executing him, given all the circumstances, serves justice or undermines it. For those calling for clemency, including jurors who sentenced him and the daughter of the man who was killed, the answer is clear: taking Burton’s life under these circumstances would compound, rather than correct, the tragedy that occurred in that AutoZone store more than three decades ago.