Vietnam’s Hidden Fear: Behind the Diplomatic Smile Lies Deep Mistrust of America

The Paradox of Partnership and Paranoia

Just one year after Vietnam elevated its relationship with the United States to the highest possible diplomatic level, a startling internal military document has revealed the stark contradiction at the heart of Hanoi’s foreign policy. While publicly celebrating a “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership” with Washington, Vietnam’s Ministry of Defense was simultaneously preparing for what it called a potential American “war of aggression.” The document, completed in August 2024 and titled “The 2nd U.S. Invasion Plan,” labels the United States as a “belligerent” power and warns military planners to remain vigilant against American intentions. This revelation, brought to light by The 88 Project—a human rights organization monitoring Vietnam—exposes not just diplomatic duplicity, but something far more profound: a deep-seated paranoia within Vietnam’s Communist leadership about external forces seeking to overthrow their government through what they call a “color revolution.” These fears reference historical uprisings like Ukraine’s 2004 Orange Revolution or the Philippines’ 1986 Yellow Revolution, where popular movements toppled existing power structures. According to Ben Swanton, co-director of The 88 Project and author of the analysis, this isn’t merely fringe thinking within Vietnam’s government. “There’s a consensus here across the government and across different ministries,” Swanton explained. “This isn’t just some kind of fringe element or paranoid element within the party or within the government.” The document represents a coordinated, government-wide perspective that views America as both partner and potential existential threat.

What Vietnam’s Military Really Thinks About American Intentions

The internal Ministry of Defense document paints a troubling picture of how Vietnam’s military establishment perceives American strategy in Asia. According to Vietnamese military analysts, the United States has pursued an increasingly aggressive posture across three presidential administrations—from Barack Obama through Donald Trump’s first term and into Joe Biden’s presidency. In their view, Washington has systematically built military and diplomatic relationships throughout Asia with one primary goal: forming a united front against China. Within this strategic framework, Vietnam sees itself as a potential chess piece that America wants to position against Beijing. The document acknowledges that “currently there is little risk of a war against Vietnam,” but quickly adds a critical caveat: “due to the U.S.’s belligerent nature we need to be vigilant to prevent the U.S. and its allies from ‘creating a pretext’ to launch an invasion of our country.” This language reveals how Vietnamese planners believe America operates—not through straightforward military aggression, but through manufactured justifications for intervention. The analysts suggest that while pursuing its objective of deterring China, the U.S. and its allies are “ready to apply unconventional forms of warfare and military intervention and even conduct large-scale invasions against countries and territories that ‘deviate from its orbit.'” Perhaps most revealing is the document’s assessment that while the U.S. views Vietnam as “a partner and an important link” in its regional strategy, Washington simultaneously wants to “spread and impose its values regarding freedom, democracy, human rights, ethnicity and religion” to gradually transform Vietnam’s socialist government. This is the nightmare scenario that keeps Vietnam’s Communist leadership awake at night—not tanks rolling across borders, but ideas penetrating society and undermining their political monopoly from within.

The Color Revolution Obsession

At the core of Vietnam’s strategic anxiety lies an obsessive fear of “color revolutions”—popular uprisings that have toppled authoritarian governments around the world. This paranoia isn’t confined to classified military documents; it occasionally erupts into public view, revealing the tensions simmering beneath Vietnam’s carefully managed diplomatic surface. In June 2024, these internal conflicts spilled into the open when an army television report accused Fulbright University—an institution with American connections—of fomenting a color revolution in Vietnam. The accusation was remarkable because both U.S. and Vietnamese officials had prominently highlighted Fulbright University when the two countries upgraded their diplomatic ties. The Foreign Ministry found itself in the awkward position of defending the university against accusations from the military, exposing the deep divisions within Vietnam’s government about how to engage with America. According to Zachary Abuza, a professor at the National War College in Washington and author of “The Vietnam People’s Army: From People’s Warfare to Military Modernization?”, while Western diplomats have generally assumed Vietnam’s primary security concern is Chinese aggression, the reality is quite different. “This pervasive insecurity about color revolutions is very frustrating, because I don’t see why the Communist Party is so insecure,” Abuza observed. “They have so much to be proud of—they have lifted so many people out of poverty, the economy is humming along, they are the darling of foreign investors.” Yet despite these achievements, Vietnam’s leadership remains haunted by the possibility that external forces, particularly the United States, might support or even orchestrate an uprising against Communist rule. This fear shapes every aspect of how Vietnam approaches its relationship with Washington, creating a fundamental contradiction: Hanoi wants American economic partnership and a counterbalance to Chinese pressure, but simultaneously views American values and influence as an existential threat to the political system.

China: Rival or Acceptable Neighbor?

Interestingly, the internal documents reveal that Vietnam views China very differently than it views the United States—despite ongoing territorial disputes in the South China Sea. While China and Vietnam have genuine conflicts over maritime claims and have even fought border wars in the past, the documents portray China more as a regional rival to be managed than an existential threat like America. “China doesn’t pose an existential threat to the Communist Party (of Vietnam),” Abuza explained. The reason is straightforward: both countries are governed by Communist parties with similar political systems and a shared interest in maintaining one-party rule. “Indeed, the Chinese know they can only push the Vietnamese so far, because they’re fearful that the Communist Party can’t respond forcefully to China (and will) look weak and it will cause a mass uprising,” Abuza noted. This creates a strange dynamic where territorial violations by China are seen as manageable challenges, while American democracy promotion programs are viewed as potentially regime-ending threats. The economic relationship reinforces this complicated balance. China is Vietnam’s largest overall trading partner, while the United States is Vietnam’s largest export market. This means Hanoi must perform a delicate balancing act, maintaining diplomatic and economic ties with both powers while hedging against potential threats from either direction. Vietnam’s strategy has been described as “bamboo diplomacy”—bending with the wind but never breaking, staying flexible enough to accommodate pressure from multiple directions without committing fully to any single alignment.

How Trump’s Actions Are Reshaping Vietnamese Calculations

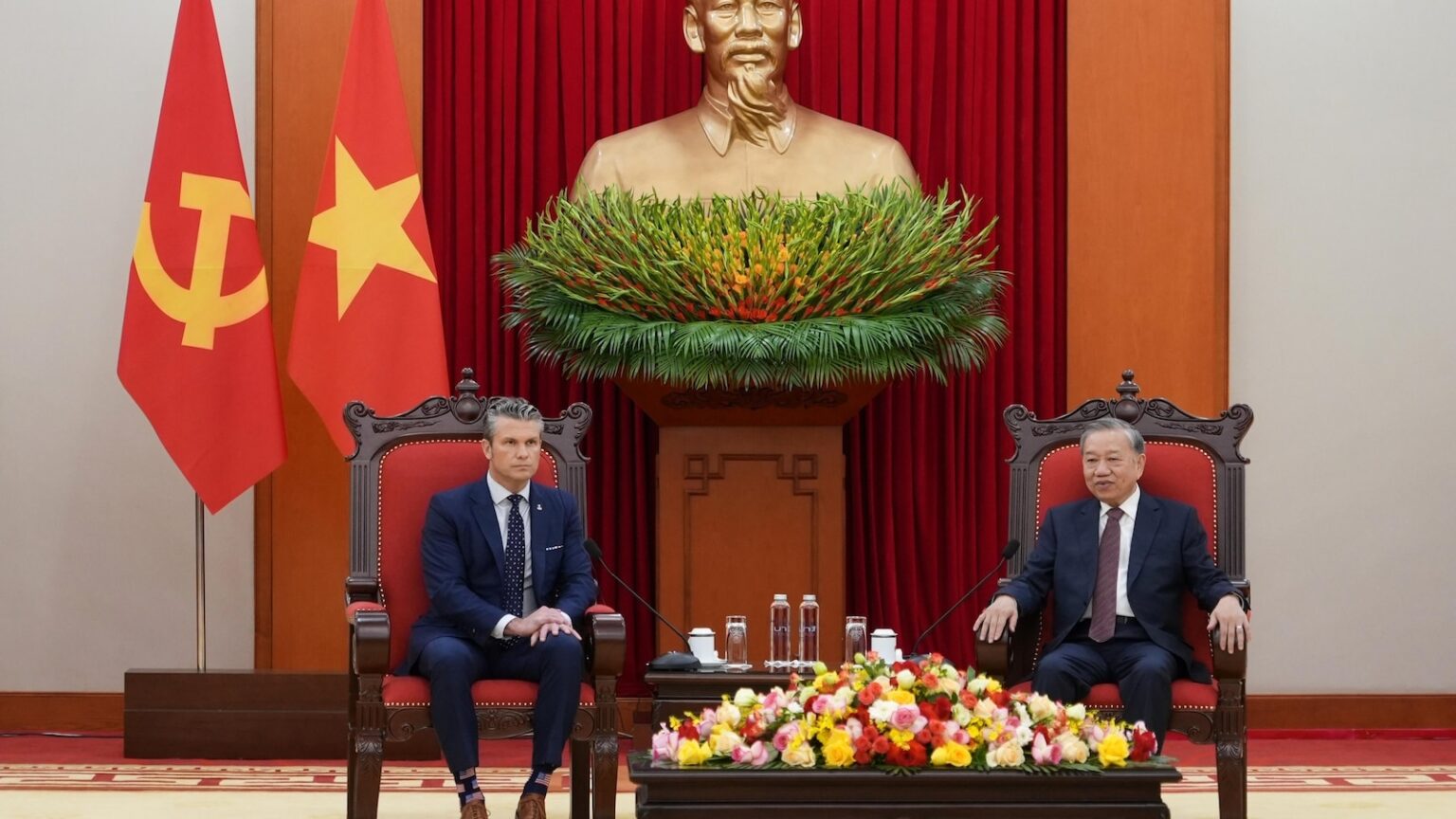

The complicated relationship between Vietnam and the United States has taken new turns during Donald Trump’s second presidency, creating both opportunities and fresh anxieties for Hanoi’s leadership. Under Vietnamese leader To Lam, who became Communist Party general secretary around the same time the military document was written, Vietnam has actually moved to strengthen ties with the United States, particularly with the Trump administration. According to Nguyen Khac Giang of Singapore’s ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute research center, Lam has demonstrated unusual willingness to engage with Trump. The Vietnamese leader almost immediately accepted Trump’s invitation to join the Board of Peace—a surprisingly swift decision given that Vietnam’s foreign policy moves are typically calibrated with careful attention to how Beijing might react. Trump’s business dealings in Vietnam have also expanded dramatically, with his family business breaking ground on a $1.5 billion Trump-branded golf resort and luxury real estate project in northern Hung Yen province. However, Trump’s unpredictable military actions have simultaneously reinforced Vietnamese conservatives’ deepest fears about American intentions. The administration’s military operation to capture former Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro sent shock waves through Hanoi’s political establishment. Even more concerning for Vietnam would be any U.S. military action involving Cuba, a fellow Communist state with which Vietnam maintains close ties. “Cuba is very sensitive,” Giang explained. “If something happens in Cuba, it will send shock waves through Vietnam’s political elites. Many of them have very strong, intimate ties with Cuba.” Additionally, the Trump administration’s cuts to the U.S. Agency for International Development disrupted long-running cooperative projects in Vietnam, including efforts to clean up soil contaminated with deadly dioxin from Agent Orange and to remove unexploded American munitions and landmines—painful legacies of the Vietnam War that ended in 1975. These cuts damaged trust and reminded Vietnamese officials that American commitments can evaporate with changes in administration or political winds.

The Long Shadow of History and an Uncertain Future

The Vietnamese military’s persistent suspicion of American intentions cannot be understood without acknowledging the long shadow cast by the Vietnam War. As Abuza noted, the Vietnamese military “still has a very long memory” of the conflict that ended in 1975 with American withdrawal and the unification of Vietnam under Communist rule. That historical experience shapes how military planners view contemporary American actions, creating a lens of suspicion through which even benign initiatives can appear threatening. The document titled “The 2nd U.S. Invasion Plan” provides what Swanton called “one of the most clear-eyed insights yet into Vietnam’s foreign policy,” showing that “far from viewing the U.S. as a strategic partner, Hanoi sees Washington as an existential threat and has no intention of joining its anti-China alliance.” Neither Vietnam’s Foreign Ministry nor the U.S. State Department directly addressed the military document when asked for comment. The State Department instead emphasized the partnership agreement, saying it “promotes prosperity and security for the United States and Vietnam” and that “a strong, prosperous, independent and resilient Vietnam benefits our two countries and helps ensure that the Indo-Pacific remains stable, secure, free and open.” Looking ahead, the contradictions in Vietnam’s approach seem likely to persist. As Abuza observed, the first year of Trump’s second term has probably left Vietnamese officials “confused by the Trump administration, which has downplayed human rights and democracy promotion, but at the same time been willing to violate the sovereignty of states and remove leaders they don’t like.” This confusion captures the essential dilemma facing Vietnam: how to engage economically and diplomatically with a powerful partner whose political values and unpredictable actions pose what Hanoi’s leadership perceives as fundamental threats to their continued rule. The revelation of this internal military document doesn’t necessarily mean Vietnam will change its outward diplomatic posture, but it does expose the deep suspicion and fear underlying the smiles and handshakes of official state visits, reminding us that in international relations, what governments say publicly and what they believe privately can be dramatically different things.