Understanding Measles Risk in Your Neighborhood: A Revolutionary New Tool

Interactive Map Reveals Vaccination Gaps Across America

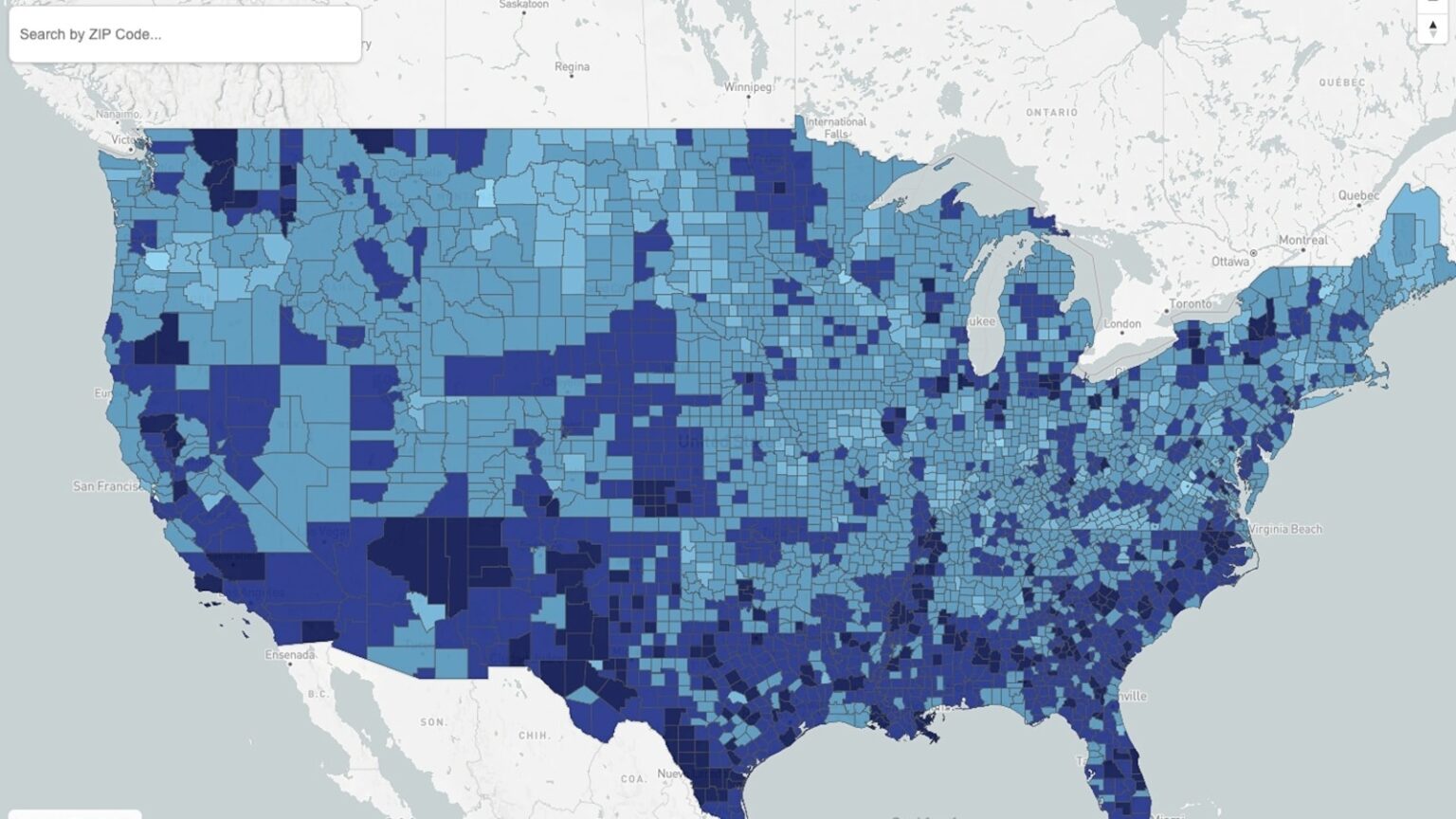

For the first time in public health history, Americans can now get a detailed picture of measles vaccination levels right in their own backyard. As measles cases have surged to levels not seen in over three decades, a groundbreaking interactive map has been developed that allows anyone to type in their ZIP code and discover the estimated percentage of vaccinated neighbors in their community. This innovative tool comes at a critical time when the United States is grappling with a measles resurgence that has left many families anxious about their vulnerability to this highly contagious disease.

This remarkable mapping project emerged from a collaborative effort among researchers from some of America’s most prestigious medical institutions, including Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard School of Medicine, HealthMap, and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. The team published their findings in the journal Nature Health, making the data accessible not only to scientists and public health officials but to everyday Americans who want to understand their risk. The map is also available on the HealthMap epidemiological website, providing a user-friendly interface that transforms complex vaccination data into information that families can actually use when making decisions about their health and safety.

According to Dr. John Brownstein, a co-author of the study and an epidemiologist who serves as an ABC News medical contributor, what we’re currently witnessing represents just “the tip of the iceberg in terms of risk.” His words underscore a troubling reality: many communities across the United States have vaccination rates far below the levels needed to prevent outbreaks. The map serves as what Brownstein calls “an unfortunate sort of crystal ball into the future of where we’ll see these future outbreaks,” offering a glimpse into which neighborhoods and regions are most vulnerable to the continued spread of this preventable disease.

The Alarming Numbers Behind the Measles Resurgence

The statistics paint a sobering picture of America’s current measles crisis. In 2024, the United States recorded its highest number of measles cases since 1992, with a staggering 2,242 infections reported across 44 states. What makes these numbers particularly concerning is that an estimated 93% of cases occurred among people who were either completely unvaccinated or whose vaccination status was unknown, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This pattern makes it crystal clear that vaccination status is the single most critical factor in determining whether someone contracts measles.

The outbreak situation has deteriorated rapidly over just a few years. While 2023 saw only four measles outbreaks nationwide, that number jumped to 16 in 2024, and then exploded to nearly 50 outbreaks in 2025. Almost 90% of the 2025 cases were associated with these outbreaks, demonstrating how quickly the virus can spread when it gains a foothold in communities with insufficient vaccination coverage. The CDC has long maintained that vaccine coverage of at least 95% with both doses of the measles vaccine is necessary to prevent outbreaks and protect communities through what’s known as herd immunity. Unfortunately, many parts of the country are falling dangerously short of this threshold.

The human toll of this resurgence extends beyond case numbers. Last year marked a tragic milestone with at least three measles deaths recorded—the first U.S. deaths from measles in a decade. Two of these victims were unvaccinated school-aged children in Texas, while the third was an unvaccinated adult in New Mexico. These deaths serve as a heartbreaking reminder that measles is not just an inconvenient childhood illness but a potentially fatal disease that we once had firmly under control in the United States. Measles was declared eliminated from the country in 2000, a public health triumph that is now under serious threat.

Hot Spots and Cold Spots: A Geographic Picture of Risk

To create their risk assessment map, the research team employed sophisticated statistical modeling techniques. They started with a nationally representative sample of more than 22,000 adults with children under age 5 who had received one or more doses of the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. Using this data, they generated county-level and ZIP code-level estimates of MMR vaccination coverage. The researchers then classified these areas into five distinct risk categories, ranging from “lowest risk” areas where 85% or more of young children have received at least one MMR dose, to “very high risk” zones where fewer than 60% of children under age 5 have been vaccinated.

The geographic patterns that emerged from this analysis are striking. The researchers identified vaccination “hot spots”—areas of dangerously low vaccination coverage—scattered across West Texas, southern New Mexico, parts of Mississippi, and throughout the rural Southeast. Many of these high-risk areas align disturbingly well with locations that have already experienced recent measles outbreaks. For instance, Gaines County in Texas, which served as the epicenter of last year’s major outbreak in that state, fell into the second-highest risk category with only 60% to 69% of young children receiving one or more MMR doses. Even more concerning was Lea County in New Mexico, the epicenter of that state’s outbreak, which landed in the highest risk category with fewer than 60% of young children vaccinated.

On the more encouraging side, the researchers found vaccination “cold spots”—areas with high vaccination coverage—concentrated primarily in the Northeast and Upper Midwest. Maine provides an excellent example of a state performing well on vaccination coverage. Not a single county in Maine was placed in a category higher than medium risk, with every county reporting that at least 70% to 79% of young children had received at least one MMR dose. These geographic variations highlight how measles risk is not evenly distributed across the country. As Dr. Brownstein emphasized, “We know that outbreaks are highly local, so to be able to respond to an outbreak that is highly localized, you need highly localized data, and this is really a first-of-a-kind study to do this.”

The Troubling Decline in Childhood Vaccination Rates

The measles resurgence isn’t happening in a vacuum—it’s occurring against a backdrop of steadily declining childhood vaccination rates that began before the COVID-19 pandemic and has accelerated since. According to CDC data, the percentage of kindergarteners receiving the MMR vaccine has dropped from 95.2% in 2019 to an estimated 92.5% in the most recent school year. While a difference of less than three percentage points might not sound dramatic, it translates to nearly 300,000 kindergarteners who lack protection against one of the most contagious infectious diseases known to humanity. To put measles’ contagiousness in perspective: if one person has measles, they can infect nine out of ten people around them who aren’t vaccinated. The virus is so hardy that it can linger in a room for at least two hours after an infected person has left.

Compounding this problem is the rising number of families choosing to opt out of vaccinations for non-medical reasons. New research published in JAMA reveals that the share of children with non-medical vaccine exemptions has surged from just 0.6% in 2020-21 to 3.1% in 2023-24. This five-fold increase represents a significant shift in how some American families view childhood vaccinations. While public health officials acknowledge that vaccination is ultimately a personal choice, they caution that these individual decisions have collective consequences. The rate of vaccination in a community directly impacts how easily a virus like measles can spread, affecting not just those who choose not to vaccinate but everyone around them.

Dr. Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, has pointed out the stark reality of living in a community with low vaccination rates: “If you’re surrounded by a lot of people who aren’t vaccinated, you’re at risk, and much greater risk, because they have a much greater chance of spreading the virus to you.” He referenced a study of an early 2000s measles outbreak in the Netherlands that found unvaccinated people were 224 times more likely to get infected than vaccinated people. But here’s the crucial finding: even vaccinated individuals faced much higher risk when living in communities with lower overall vaccination rates. This is why the concept of herd immunity matters so much—it’s not just about protecting yourself, but about creating a community shield that protects everyone, especially those who cannot be vaccinated, such as newborns and people with certain medical conditions.

Making Sense of Your Personal Risk

Dr. Eric Zhou, co-author of the study and assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, expressed hope that this new tool will empower parents to make more informed decisions: “We certainly hope, with all of this new information, parents can make more informed decisions about their children’s vaccination.” The ability to see localized vaccination data represents a significant advancement in public health transparency and education. Rather than relying on national or even state-level statistics that might not reflect conditions in your specific neighborhood, families can now access estimates that are relevant to their daily lives—their school districts, their shopping areas, their communities.

However, the researchers have been careful to acknowledge the limitations of their mapping tool. The risk levels shown are estimates based on statistical modeling, not exact measurements of every individual in a community. Additionally, individual risk varies based on numerous factors beyond just community vaccination rates, including a person’s own vaccination status, age, immune system health, and exposure patterns. The vaccination rates also include children under one year old who aren’t yet eligible for the MMR vaccine, which can affect the accuracy of the estimates. Despite these limitations, the map represents the most detailed and accessible picture of measles vaccination coverage that has ever been available to the American public.

Looking Forward: Using Data to Protect Communities

The ultimate value of this mapping project extends beyond individual decision-making. Public health officials can use this data to identify vulnerable communities and target their limited resources where they’re needed most. Instead of taking a one-size-fits-all approach to measles prevention, health departments can focus educational campaigns, vaccination clinics, and outbreak response preparations on the areas that the data indicates are most at risk. This precision approach to public health could prove crucial as health departments face budget constraints and need to maximize the impact of every dollar spent.

As Dr. Zhou noted, “Hopefully [this] will help provide more up-to-date information, more localized information, for not only the public, but also the government agencies to make the best decisions that work for everyone.” The map serves as both a warning and a roadmap—showing us where we’re vulnerable and pointing the way toward solutions. For families in high-risk areas, it might motivate conversations with pediatricians about ensuring children are up to date on vaccinations. For schools and childcare centers, it could inform policies around vaccination requirements and outbreak response plans. For entire communities, it might spark discussions about how to rebuild the herd immunity that once made measles a disease of the past in America.

The measles resurgence we’re experiencing didn’t happen overnight, and reversing it won’t be instantaneous either. But with tools like this interactive map, Americans now have access to the kind of detailed, localized information that can drive meaningful change. Whether you’re a parent trying to protect your children, a healthcare provider serving your community, or a public health official working to prevent the next outbreak, this map offers valuable insights into where we stand in the fight against measles—and how far we still need to go to reclaim the victory over this disease that we achieved just 25 years ago.