The Retirement Crisis Facing American Workers: A Wake-Up Call for Millions

A Shocking Reality: Most Americans Have Almost Nothing Saved

The numbers are sobering and paint a troubling picture of what retirement might look like for millions of hardworking Americans. According to recent research from the National Institute on Retirement Security, the typical American worker has saved less than $1,000 for their golden years—a figure that should set off alarm bells across the country. This isn’t just about people who haven’t started saving yet; this statistic includes everyone from young workers just starting out to those approaching retirement age, and it accounts for both people with 401(k) plans and the staggering 56 million workers who don’t have access to any employer-sponsored retirement plan at all. When researchers looked at all working adults between ages 21 and 64, they found the median retirement savings sat at just $955. To put this in perspective, Americans themselves believe they’ll need around $1.5 million to retire comfortably—meaning the average worker has saved less than one-tenth of one percent of what they’ll actually need. Even among those fortunate enough to have some retirement savings set aside, the median balance is only $40,000, which might sound reasonable until you realize this has to stretch across what could be twenty or thirty years of retirement. This financial reality is already showing its effects in heartbreaking ways, with the poverty rate among seniors climbing to 15% in 2024, making older Americans the age group most likely to live in poverty.

The Retirement Savings Gap Across All Ages

What makes this crisis particularly concerning is that it’s not just affecting young workers who have decades to course-correct. The research reveals that even Americans in their prime earning years and those approaching retirement haven’t managed to build the nest eggs they need. Financial experts at Fidelity suggest some helpful rules of thumb: by age 30, you should have saved the equivalent of one year’s salary; by 35, double that amount; and by the time you reach 60, you should have accumulated eight times your annual income to ensure a comfortable retirement. Unfortunately, reality falls devastatingly short of these benchmarks. Workers between 55 and 64—those who should be in their peak savings years and are just a few years away from retirement—have managed to save only 19% of what they should have accumulated by this point in their lives. This means that a worker who should have $400,000 saved might only have around $76,000, leaving them facing an impossible gap to close with just a few working years remaining. The problem isn’t simply that younger workers haven’t gotten serious about saving yet; it’s that workers across all age groups are falling behind, and older workers aren’t significantly better off than their younger counterparts, despite having had more years to save and benefit from compound interest.

Why So Many Americans Are Left Behind

The retirement savings crisis doesn’t affect all Americans equally, and understanding who gets left behind reveals fundamental problems with how we’ve structured retirement security in this country. The stark reality is that our retirement system works reasonably well for some people while completely excluding millions of others. Approximately 56 million American workers—more than one-third of the workforce—lack access to an employer-sponsored retirement plan like a 401(k). These aren’t necessarily people who are choosing not to save; they’re people who work for employers that don’t offer retirement benefits, or they’re self-employed, working part-time, or in gig economy jobs that don’t come with traditional benefits. The research makes clear that if Americans aren’t saving through their employer, they’re probably not saving at all. This makes sense when you consider the advantages of employer-sponsored plans: automatic payroll deductions that make saving effortless, potential employer matching contributions that provide free money, and tax advantages that make retirement saving more attractive than putting money in a regular savings account. Without these built-in advantages and the behavioral nudge of automatic enrollment, most people simply don’t get around to opening and regularly contributing to individual retirement accounts, especially when they’re living paycheck to paycheck and facing immediate financial pressures.

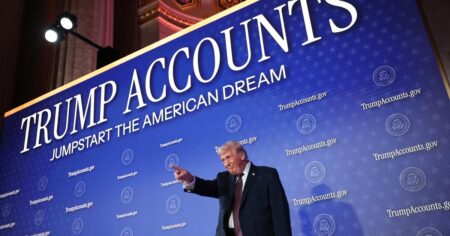

The Trump Accounts Initiative and Its Limitations

Against this backdrop of retirement insecurity, the Trump administration has introduced what they’re calling “Trump Accounts,” designed to help millions of children build savings that could eventually be used for buying a home, funding education, starting a business, or even retirement. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has promoted these accounts as a potential solution to help future generations build wealth from an early age. While this initiative might provide some benefit to children born now who could accumulate savings over decades, it does absolutely nothing to address the immediate crisis facing current workers, especially those already in their 40s, 50s, and 60s who are staring down retirement with virtually nothing saved. The program represents a long-term approach to a problem that demands both immediate intervention and systemic reform. The millions of Americans currently working with insufficient retirement savings need solutions now, not programs that might help their children or grandchildren decades down the road. Additionally, while starting children off with savings accounts sounds appealing, it doesn’t address the fundamental structural problems that leave 56 million workers without access to employer retirement plans, or the broader economic issues of stagnant wages, rising living costs, and the erosion of traditional pension plans that once provided guaranteed retirement income.

The Critical Role of Social Security and Its Uncertain Future

Given that most Americans have saved almost nothing for retirement, Social Security has become not just important but absolutely critical for keeping seniors housed, fed, and out of poverty. The program was originally designed to supplement retirement savings and pensions, but for millions of Americans it has become their primary or even sole source of retirement income. However, many Americans fundamentally misunderstand what Social Security can and cannot do for them in retirement. A 2025 survey found that one in five Americans mistakenly believe Social Security will provide all the income they need in retirement, when in reality it typically provides only about half of the average senior’s annual income. For millions of seniors, Social Security provides even more than half their income, making them almost entirely dependent on these benefits. This makes the program’s looming funding crisis not just a policy problem but a potential catastrophe for retirement security. Without congressional action, Social Security’s trust fund is projected to be depleted by 2034, which would trigger an automatic 20% reduction in benefits across the board. For someone receiving $2,000 per month from Social Security, this would mean a sudden drop to $1,600—a devastating cut for someone already struggling to make ends meet on a fixed income.

Finding Solutions Before It’s Too Late

Addressing America’s retirement crisis will require action on multiple fronts, from shoring up Social Security to expanding access to retirement savings plans and helping current workers catch up on their savings. For Social Security, lawmakers have several options to address the funding gap, though all involve difficult political choices. They could raise the payroll tax rate, asking workers and employers to contribute more to the system. They could increase the retirement age, requiring people to work longer before claiming full benefits. Or they could lift or eliminate the current cap on earnings subject to Social Security taxes, which in 2026 is set at $184,500, meaning income above that threshold isn’t taxed for Social Security purposes. This last option would ask higher earners to contribute more while leaving benefits unchanged for most Americans. Beyond Social Security, policymakers need to address the reality that 56 million workers lack access to employer retirement plans by creating portable retirement accounts that follow workers from job to job, expanding automatic enrollment programs that have proven successful at boosting participation, or establishing state-sponsored retirement plans for workers whose employers don’t offer them. For individual workers, the message is clear: even small amounts saved regularly can make a difference, especially when started early enough to benefit from compound growth. The retirement crisis didn’t develop overnight, and solving it will require sustained effort, political courage, and a recognition that retirement security isn’t just an individual responsibility but a collective challenge that affects our entire society’s wellbeing as our population ages.