Federal Court Restricts Use of Tear Gas Against Portland Protesters

A Landmark Ruling at America’s Constitutional Crossroads

In a significant decision that addresses the tension between public safety and constitutional rights, a federal judge in Oregon has temporarily blocked federal officers from using tear gas and other crowd-control weapons against protesters gathered outside Portland’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement facility. U.S. District Judge Michael Simon issued the restraining order on Tuesday, days after federal agents deployed chemical irritants against what local officials described as a peaceful gathering that included young children among the demonstrators. The judge’s order, which will remain in effect for 14 days, establishes strict limitations on when and how federal officers can use force against protesters. According to the ruling, chemical or projectile munitions can only be deployed when an individual poses a clear and immediate threat of physical harm. Furthermore, officers are prohibited from aiming such weapons at vulnerable areas like the head, neck, or torso unless the situation legally justifies the use of deadly force. In his written decision, Judge Simon framed the moment as a pivotal one for the nation, describing America as standing “at a crossroads” where fundamental democratic principles must be protected and respected by an independent judiciary committed to upholding the rule of law.

Understanding the Scope of Restricted Weapons and Tactics

The judge’s temporary restraining order covers an extensive array of weapons and crowd-control devices that federal officers have been using at protests. The prohibited items include kinetic impact projectiles, which are designed to cause pain and compliance without penetrating the skin, as well as pepper ball and paintball guns that have been modified for law enforcement use. The order also restricts the use of pepper spray and oleoresin capsicum spray, both of which cause intense burning sensations and temporary incapacitation. Additionally, tear gas and other chemical irritants that disperse crowds by causing severe discomfort to the eyes, nose, and respiratory system are now severely limited. The ruling extends to various types of ammunition and delivery systems, including soft nose rounds, 40mm and 37mm launchers typically used to fire tear gas canisters, and less-lethal shotguns. Even flashbang grenades, which create disorienting noise and light, along with Stinger and rubber ball grenades, fall under the restrictions. This comprehensive list demonstrates the wide range of weapons that have been deployed against protesters and reflects the court’s concern about the potential for serious injury and the chilling effect such tactics have on citizens exercising their constitutional rights to free speech and peaceful assembly.

The ACLU Lawsuit and Stories of Ordinary Citizens Harmed

The court’s decision came in response to a lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union of Oregon, representing both protesters and freelance journalists who have been documenting demonstrations at the ICE building. The lawsuit names the Department of Homeland Security, its secretary Kristi Noem, and President Trump as defendants, arguing that federal officers have used excessive force as retaliation against protesters, thereby violating their First Amendment rights. The complaint includes deeply troubling accounts of ordinary citizens who were injured while peacefully exercising their constitutional rights. Among the plaintiffs are Richard and Laurie Eckman, a married couple in their eighties who joined a peaceful march to the ICE building last October. Federal officers launched chemical munitions at the crowd, striking 84-year-old Laurie Eckman in the head with a pepper ball that caused bleeding. She required hospital treatment and received instructions for caring for a concussion, attending to her injuries with blood-stained clothing and hair. The munitions also struck her 83-year-old husband’s walker, demonstrating the indiscriminate nature of the force being used. Another plaintiff, Jack Dickinson, has become a familiar presence at protests where he appears in a chicken costume. According to the complaint, federal officers have repeatedly targeted him with munitions despite his posing no threat, shooting at his face respirator and his back, and launching a tear-gas canister that sparked near his leg, burning a hole in his costume. Two freelance journalists, Hugo Rios and Mason Lake, report being hit with pepper balls and tear-gassed even while clearly identified as members of the press, raising serious concerns about attacks on press freedom and the public’s right to know what happens at these demonstrations.

The Federal Response and Clash of Perspectives

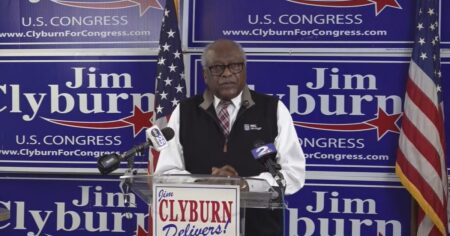

The Department of Homeland Security has defended the actions of federal officers, maintaining that they have acted appropriately within constitutional bounds. In a statement responding to the court ruling, DHS spokesperson Tricia McLaughlin asserted that federal officers have “followed their training and used the minimum amount of force necessary to protect themselves, the public, and federal property.” The department drew a sharp distinction between peaceful assembly, which it acknowledged is protected by the First Amendment, and rioting, which it claims is not protected speech. McLaughlin stated that DHS is taking “appropriate and constitutional measures to uphold the rule of law and protect our officers and the public from dangerous rioters.” This characterization stands in stark contrast to descriptions provided by local officials and eyewitnesses. Portland Mayor Keith Wilson praised the court’s ruling, stating it “confirms what we’ve said from the beginning” about federal agents using “unconscionable levels of force against a community exercising their constitutional right to free expression.” The mayor had previously demanded that ICE leave the city following Saturday’s incident, when federal officers deployed chemical munitions at what he described as a “peaceful daytime protest where the vast majority of those present violated no laws, made no threat, and posed no danger to federal forces.” This fundamental disagreement about the nature of the protests—whether they constitute peaceful assembly or dangerous rioting—lies at the heart of the legal and political conflict surrounding federal enforcement actions.

A National Pattern of Protests and Legal Challenges

The situation in Portland reflects a broader national phenomenon, as cities across the United States have witnessed surges in demonstrations against federal immigration enforcement policies. The protests have been met with varying levels of force from federal agents, prompting legal challenges in multiple jurisdictions. Federal courts in different parts of the country have been grappling with similar questions about the appropriate limits on law enforcement tactics at protests. Last month, a federal appeals court suspended a decision that had prohibited federal officers from using tear gas or pepper spray against peaceful protesters in Minnesota who weren’t obstructing law enforcement activities. Similarly, in November, an appeals court halted a ruling from a federal judge in Chicago that had restricted federal agents from using riot control weapons such as tear gas and pepper balls unless necessary to prevent an immediate threat. A related lawsuit brought by the state of Illinois is currently pending before the same judge. The protests themselves have been driven by concerns about aggressive immigration enforcement, with Minneapolis emerging as another flashpoint where, in recent weeks, federal agents killed two people: Alex Pretti and Renee Good. These deaths have intensified scrutiny of federal tactics and added urgency to questions about accountability and the appropriate balance between enforcement and civil liberties.

The Broader Constitutional Questions at Stake

Judge Simon’s decision goes beyond the immediate question of crowd-control tactics to address fundamental principles of American democracy. In his written order, he eloquently described the values that should characterize “a well-functioning constitutional democratic republic,” including the protection, respect, and even celebration of free speech, courageous journalism, and nonviolent protest. His assertion that an independent judiciary has a responsibility to help the nation “find its constitutional compass” frames the ruling as more than just a procedural matter—it positions the courts as essential guardians of democratic norms during a period of significant tension. The ACLU’s complaint powerfully captures what’s at stake, arguing that “Defendants must be enjoined from gassing, shooting, hitting and arresting peaceful Portlanders and journalists willing to document federal abuses as if they are enemy combatants.” This language highlights concerns that federal responses to domestic protests have adopted tactics more appropriate for military conflict zones than for policing American citizens exercising constitutional rights. The complaint further argues that federal actions “have caused and continue to cause Plaintiffs irreparable harm, including physical injury, fear of arrest, and a chilling of their willingness to exercise rights of speech, press, and assembly.” This chilling effect—the phenomenon whereby people refrain from exercising their rights due to fear of government retaliation—represents a serious threat to democratic participation. As this temporary restraining order takes effect for the next two weeks, it will provide a test case for whether judicial intervention can effectively protect constitutional rights while still allowing for legitimate law enforcement needs, potentially setting important precedents for how protests are policed throughout the country.