The Turpin Siblings: From One Nightmare Into Another

Escaping a House of Horrors Only to Face More Abuse

The Turpin family case shocked the world in January 2018 when 17-year-old Jordan Turpin bravely escaped through a window of her family’s Perris, California home and dialed 911, ultimately freeing herself and her twelve siblings from years of unimaginable torture. What authorities discovered inside that house was beyond horrifying: thirteen siblings, ranging in age from 2 to 29, had been subjected to brutal violence, systematic starvation, sleep deprivation, and complete denial of basic human needs like hygiene, education, and healthcare. Their parents, David and Louise Turpin, had created a prison within their own home, and their children paid the price with years of their lives. The parents eventually pleaded guilty to fourteen charges, including torture and false imprisonment, receiving sentences of 25 years to life in 2019. But for six of the youngest Turpin children, their nightmare was far from over—in fact, it was about to begin again in a place that was supposed to represent safety and healing.

Now, over seven years after their initial rescue, three of those siblings—Julissa, 19, Jolinda, 20, and their brother James, 24—are breaking their silence about what happened after they entered the foster care system. In their first interview with ABC News, they reveal the devastating truth: the foster home where they were placed became another house of horrors. “I genuinely just wanted to be safe,” Julissa told ABC News, expressing the simple, heartbreaking desire that every child deserves but that she was denied twice over. Their story raises troubling questions about a system designed to protect vulnerable children and exposes the catastrophic failures that allowed already traumatized victims to be placed directly in harm’s way once again. The siblings’ courage in speaking out follows in the footsteps of their sisters Jennifer and Jordan Turpin, who first shared their story with Diane Sawyer over four years ago, detailing the beatings and starvation they endured in their biological family’s home.

The Depth of Trauma from Their Biological Parents

To understand the full weight of what these children endured, it’s important to revisit the conditions from which they were rescued. James Turpin was so severely emaciated when authorities found him that he could barely walk—a 24-year-old man reduced to physical frailty typically seen only in extreme famine conditions. The psychological toll was equally devastating. “I was having nightmares that they were, like, killing us, basically,” James recalled, his words painting a picture of children living in constant terror within their own home. Julissa’s memories are equally haunting: “Towards the end, you know, I would always, like, cry at night. And I would beg Jesus to, like, take me,” she shared, describing how she felt death approaching and actually prayed for it as a release from her suffering. These weren’t just difficult childhoods—these were children living in a prolonged state of torture, their bodies and spirits systematically broken by the people who should have protected them most.

The rescue in January 2018 should have marked the beginning of healing, recovery, and finally experiencing the childhood they’d been denied. For six of the younger siblings, including Julissa, Jolinda, and James, the path forward led to a foster home—a placement that social services professionals assured would provide the safety, stability, and care they desperately needed. Instead, they walked from one nightmare directly into another, a transition that represents one of the most profound failures of the child welfare system imaginable. These children, already bearing the scars of years of abuse, were about to learn that the systems designed to protect them could be just as dangerous as the family they’d been rescued from.

A Foster Home That Became Another Prison

Julissa was just eleven years old when she moved into her new foster home, still processing the trauma of her biological family while trying to embrace hope for a better future. That hope was shattered on the very first night when her new foster father told her she was “sexy.” “I didn’t know very much, but I did know that that didn’t feel right,” she told ABC News, her instincts correctly warning her of danger despite her limited understanding of the world. “And I did feel very uncomfortable. And it made me feel so unsafe in the home.” Her discomfort was tragically justified—the inappropriate comments escalated to physical abuse as the foster father went on to inappropriately touch and forcibly kiss her. A child who had just escaped years of torture was now experiencing sexual abuse in the very place meant to heal her.

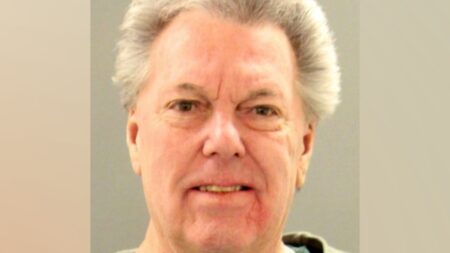

The foster parents who took in these six vulnerable Turpin children—Marcelino Olguin, his wife Rosa Olguin, and their daughter Lennys Olguin—eventually faced justice, though many would argue far too late and with consequences far too lenient for the damage they inflicted. In 2024, all three pleaded guilty to child endangerment and false imprisonment. Marcelino Olguin also pleaded guilty to lewd and lascivious acts on a child under 14, receiving a seven-year state prison sentence, while Rosa and Lennys Olguin each received just four years of probation. The contrast between their relatively light sentences and the lifetime of trauma they inflicted on children who had already suffered unimaginable abuse highlights the ongoing challenges in holding those who harm children truly accountable. Meanwhile, the Turpin siblings were left to pick up the pieces of their shattered lives once again, having learned the bitter lesson that official placement in a “safe” home provides no guarantee of actual safety.

System Failures That Enabled Continued Abuse

Perhaps the most infuriating aspect of this tragedy is that it was entirely preventable. The six Turpin siblings sued Riverside County and ChildNet—the private foster care agency tasked with placing them in an appropriate home—alleging they suffered “severe abuse and neglect” for years in the foster family’s care. The lawsuit resulted in a financial settlement, though notably, neither the county nor the agency admitted any wrongdoing. But the complaints filed in the case revealed a shocking truth: Riverside County and ChildNet allegedly knew that the foster family had “a prior history of abusing and neglecting children who had been placed in their care.” Despite this documented history, despite knowing these foster parents were “unfit,” the Turpin siblings were placed with them anyway. It’s a failure so profound that it challenges belief—how could the very agencies charged with protecting these already-traumatized children knowingly place them with foster parents who had previously harmed children in their care?

A comprehensive 630-page report issued in 2022 by outside investigators hired by Riverside County confirmed what many had suspected: the thirteen Turpin siblings had been systematically “failed” by the social services system that was supposed to care for them and help them transition into society. “Some of the younger Turpin children were placed with caregivers who were later charged with child abuse,” the report documented, a damning indictment stated in bureaucratic language that barely hints at the human suffering behind those words. The report also found that “some of the older siblings experienced periods of housing instability and food insecurity as they transitioned to independence”—meaning that children who had been starved by their biological parents then experienced hunger again under the supervision of the agencies meant to protect them. The Riverside County Board of Supervisors moved to implement the report’s recommendations for improving services, but for the Turpin siblings, these reforms came far too late to prevent their continued suffering.

Reforms and Accountability, But Can Trust Be Restored?

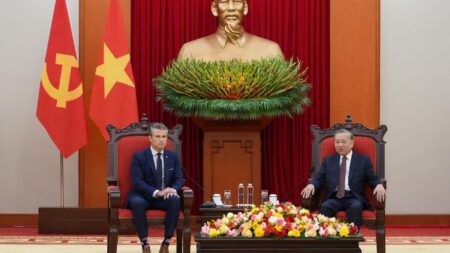

In response to the failures exposed by the Turpin case, Riverside County has implemented various reforms, though questions remain about whether these changes go far enough. County Executive Officer Jeff Van Wagenen acknowledged in a January 2025 statement to ABC News that “the abuse these children suffered in both their biological and adoptive homes was tragic and unacceptable.” He outlined reforms including strengthened coordination between child welfare and law enforcement “so that high-risk situations are handled quickly, clearly, and consistently,” updated policies in areas “where failures can occur,” and improved training for staff regarding interviews and awareness of recording devices. Van Wagenen emphasized that “reform does not work without enough trained people to do the job” and stressed the importance of “investing in trained social workers” to achieve “safer outcomes” for children. “Riverside County’s commitment remains firm: to protect children, elevate their voices, and ensure every decision is grounded in protection, compassion and stability,” he stated.

ChildNet, the foster care agency involved in the placement, issued its own statement expressing sympathy but notably deflecting responsibility. “We are deeply sorry for the pain they suffered, and we sincerely hope they continue to heal, thrive, and find peace,” the agency said. However, ChildNet emphasized that “during the time the children were in ChildNet’s foster care program, there were no complaints or allegations of abuse or neglect regarding their foster placement,” adding that “the allegations raised in this matter came after the children were no longer in ChildNet’s care and after the foster care case had been closed.” This statement raises its own troubling questions: why was the case closed while the children were still in that home? Were proper follow-up procedures in place? And most importantly, how were the alleged prior issues with this foster family not identified during the placement process? These bureaucratic responses, while acknowledging past failures, still seem to miss the fundamental point: vulnerable children were knowingly placed in danger, and the system designed to protect them instead enabled their continued abuse.

Finding Their Voice and Demanding Change

Despite everything they’ve endured, the Turpin siblings are determined that their suffering will serve a purpose. Roger Booth, one of the attorneys representing the Turpins, explained that the siblings “wanted the story to get out there. They wanted to not just be sort of these nameless, faceless victims.” This desire to reclaim their narrative and use their experiences to protect other children shows remarkable strength and resilience. “I think what’s critically important here is these young people do have a voice. And they’ve chosen to use it,” Booth said. By speaking publicly about what happened to them, Julissa, Jolinda, and James are forcing society to confront uncomfortable truths about the failures of systems we trust to protect the most vulnerable among us. They’re also providing representation for countless other children who have suffered similar fates in foster care situations that were supposed to save them, not harm them further.

Jolinda Turpin perhaps best expressed the driving force behind their decision to speak out: something “good” needs to come from their experiences. “It has to, and I can’t accept it not,” she said with the quiet determination of someone who has survived the unimaginable and refuses to let that survival be meaningless. Their story will be featured in the Diane Sawyer special event “The Turpins: A New House of Horrors,” highlighting how their journey from victims to advocates continues. While no amount of reform can undo the years of abuse they suffered or restore the childhoods they were denied twice over, the Turpin siblings are fighting to ensure that future vulnerable children don’t face the same systematic failures that enabled their continued victimization. Their courage in sharing their painful story represents hope that meaningful change is possible—but only if society listens, learns, and commits to truly protecting every child placed in the care of systems designed for their safety. The Turpin siblings have found their voice; now the question is whether those with the power to reform child welfare systems will truly hear them and act accordingly.