Vietnam’s Hidden Fears: Behind the Diplomatic Smile Lies Deep Mistrust of America

A Troubling Discovery Beneath the Surface of Friendship

Just a year after Vietnam and the United States celebrated upgrading their relationship to the highest diplomatic level—a “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership” that placed America alongside Russia and China as trusted partners—a shocking internal military document has revealed what Vietnamese leaders really think when the cameras are off. The document, titled “The 2nd U.S. Invasion Plan” and completed by Vietnam’s Ministry of Defense in August 2024, paints America not as a partner but as a potential aggressor preparing for war. This revelation, brought to light by The 88 Project, a human rights organization, exposes a startling disconnect between Vietnam’s public diplomacy and its private anxieties. While American and Vietnamese officials smiled for photos and signed partnership agreements, military planners in Hanoi were simultaneously strategizing how to defend against what they called America’s “belligerent nature” and preparing for possible U.S. military intervention. The document’s existence confirms that despite decades of warming relations and growing economic ties, the ghosts of the Vietnam War and deep-seated fears about American intentions continue to haunt the corridors of power in Hanoi.

The Specter of “Color Revolution” Haunts Vietnam’s Leaders

What truly terrifies Vietnam’s Communist leadership isn’t necessarily tanks rolling across borders or missiles raining from the sky—it’s the possibility of their own people rising up against them with American encouragement. The military document and other internal papers reveal an obsession with preventing a “color revolution,” those popular uprisings that have toppled governments from Ukraine’s Orange Revolution in 2004 to the Philippines’ Yellow Revolution in 1986. To Vietnam’s conservative military faction, these movements represent America’s preferred method of regime change: funding civil society groups, promoting democratic values, and supporting opposition movements until the government collapses from within. This fear isn’t abstract paranoia confined to a few hardliners. According to Ben Swanton, co-director of The 88 Project and author of the analysis, there’s a consensus across different government ministries that the United States poses this existential threat. The Vietnamese planners believe that while America pursues economic and diplomatic engagement on the surface, it simultaneously works to “spread and impose its values regarding freedom, democracy, human rights, ethnicity and religion” with the ultimate goal of gradually dismantling Vietnam’s socialist government. This anxiety erupted into public view in June 2024 when an army television report accused Fulbright University—a U.S.-linked institution that both governments had highlighted as a symbol of bilateral cooperation—of fomenting a color revolution. The fact that Vietnam’s Foreign Ministry defended the university shows the internal struggle between those who want closer American ties and those who view such connections as dangerous Trojan horses.

America as the Ultimate Threat, China as the Manageable Rival

Perhaps most surprising to Western observers is how the Vietnamese military’s threat assessment ranks the United States above China. While headlines frequently focus on territorial disputes between Vietnam and China in the South China Sea, with Chinese vessels harassing Vietnamese fishermen and drilling operations, the internal documents reveal that Vietnamese planners view their giant northern neighbor more as a regional rival than an existential danger. China, after all, shares Vietnam’s communist ideology and political system. As Professor Zachary Abuza from the National War College explains, “China doesn’t pose an existential threat to the Communist Party of Vietnam.” The Chinese government, despite its territorial ambitions, has no interest in seeing Vietnam’s Communist Party collapse, knowing that any resulting instability could spill across their shared border. America, on the other hand, represents everything the Vietnamese Communist Party defines itself against: liberal democracy, free-market capitalism, individual rights over collective good, and a history of supporting regime change when it suits U.S. interests. The document suggests Vietnamese military planners see a progression across three American administrations—Obama, Trump’s first term, and Biden—with Washington increasingly building military relationships across Asia to “form a front against China.” While the U.S. may want Vietnam as a partner in this strategy, Vietnamese leaders suspect that America would gladly sacrifice their government if it meant advancing democratic values or gaining strategic advantage.

The Military’s Long Memory and Leadership’s Divided House

Vietnam’s military establishment, which played the decisive role in defeating American forces in 1975, maintains what Abuza calls “a very long memory” of that conflict. For many senior military officers, the idea of trusting the United States—the nation that dropped more bombs on Vietnam than were used in all of World War II, that sprayed Agent Orange across vast swaths of countryside, and that supported a brutal civil war—remains fundamentally incomprehensible. This skepticism creates tension within Vietnam’s government between the military-aligned conservative faction and more economically progressive leaders who recognize the benefits of American partnership. These internal divisions reflect a genuine dilemma facing Vietnamese leadership. The country’s economic success depends heavily on international trade and investment, with the United States serving as Vietnam’s largest export market and China as its biggest two-way trade partner. Vietnamese leaders must perform a delicate balancing act, maintaining productive relationships with both powers while trusting neither completely. Even the more progressive Vietnamese leaders, according to Abuza, tend to think: “Yes, the Americans like us, they’re working with us, they are good partners for now, but given the opportunity if there were a color revolution, the Americans would support it.” This fundamental mistrust means that no matter how many partnership agreements get signed or how many diplomatic visits occur, a significant portion of Vietnam’s leadership will continue viewing closer American ties with suspicion and preparing contingency plans for worst-case scenarios.

Recent Developments Add New Layers of Complexity

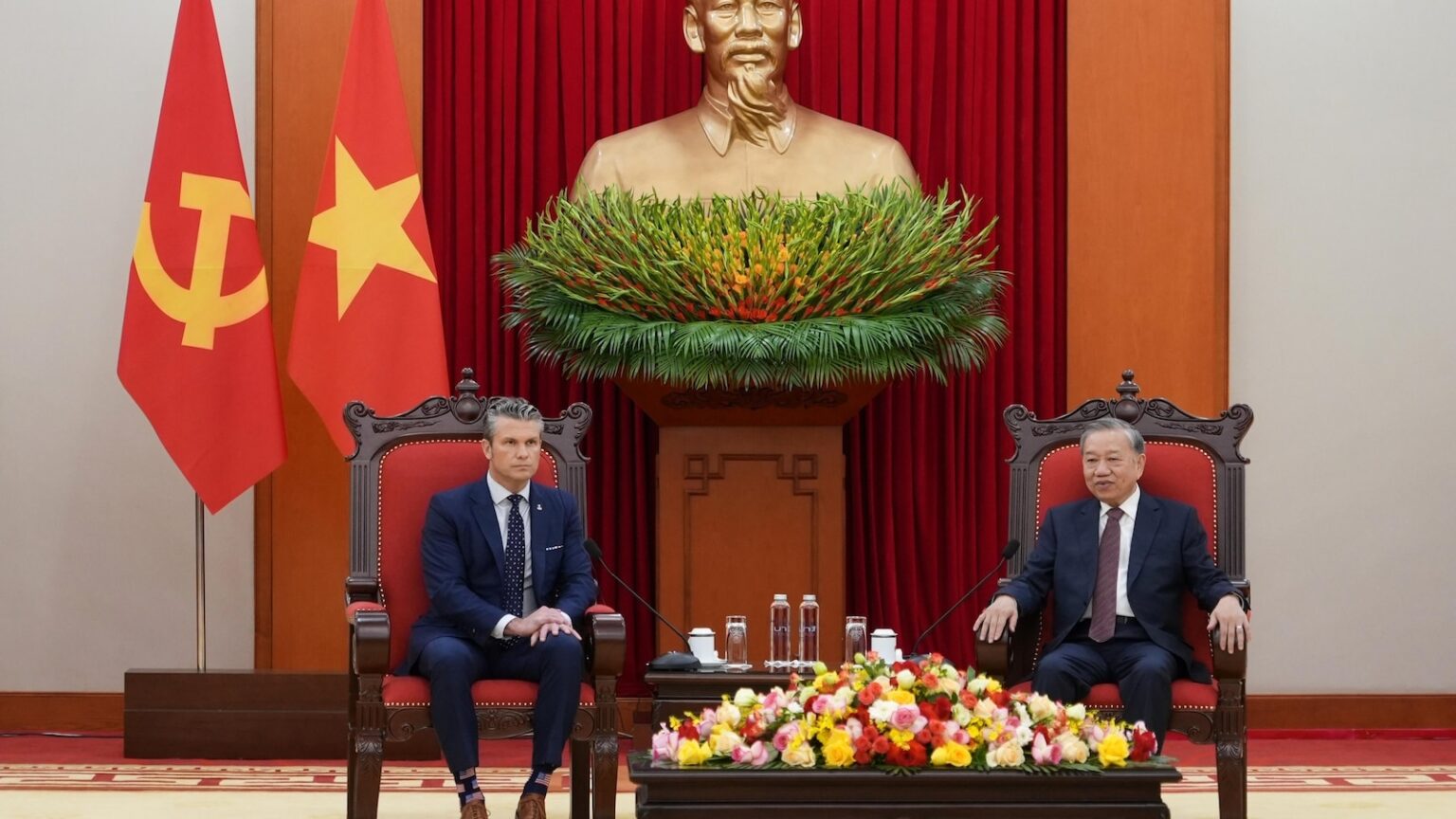

The situation has become even more complicated under Vietnam’s current leader, To Lam, who became Communist Party general secretary around the time the military document was written and was recently reappointed with expectations he’ll also assume the presidency, making him the country’s most powerful figure in decades. Under Lam’s leadership, Vietnam has paradoxically moved to strengthen ties with the United States, particularly with President Trump’s administration. The Trump family business has broken ground on a $1.5 billion golf resort and luxury real estate project in Vietnam, while Lam quickly accepted Trump’s invitation to join something called the “Board of Peace”—an unusually swift foreign policy move for a government that typically calibrates such decisions carefully to avoid Beijing’s displeasure. However, Trump’s military operation to capture former Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and potential U.S. actions involving Cuba have provided Vietnamese conservatives with fresh ammunition for their arguments against trusting Washington. Cuba holds special significance for Vietnam’s Communist leadership due to longstanding ideological ties and shared history of resisting American power. As researcher Nguyen Khac Giang notes, “If something happens in Cuba, it will send shock waves through Vietnam’s political elites.” Meanwhile, Trump administration cuts to the U.S. Agency for International Development have disrupted projects that were building goodwill, including efforts to clean up Agent Orange contamination and remove unexploded American munitions—legacy issues from the war that still affect Vietnamese people today.

The Paradox of Partnership Built on Mutual Suspicion

The revelation of Vietnam’s “2nd U.S. Invasion Plan” exposes the peculiar nature of twenty-first-century great power relationships, where countries maintain extensive diplomatic and economic partnerships while simultaneously preparing for potential conflict. Neither the Vietnamese Foreign Ministry nor the U.S. State Department would directly address the military document, with the State Department only reiterating that “a strong, prosperous, independent and resilient Vietnam benefits our two countries and helps ensure that the Indo-Pacific remains stable, secure, free and open.” This diplomatic language papers over a fundamental reality: the partnership between Washington and Hanoi rests on pragmatic interests rather than genuine trust or shared values. For America, Vietnam represents a useful partner in balancing China’s influence in Southeast Asia and a profitable market for trade and investment. For Vietnam, the United States offers economic opportunities and a counterweight to Chinese pressure, but never a relationship so close that it might give Washington leverage to demand political reforms or interfere in internal affairs. As Professor Abuza observes, Vietnamese leaders must find it “very frustrating” that despite the Communist Party’s genuine achievements—lifting millions out of poverty, sustaining strong economic growth, and attracting foreign investment—they remain “pervasively insecure” about their grip on power. Yet this insecurity drives their approach to foreign relations, ensuring that beneath every handshake and partnership agreement lies the quiet preparation for betrayal. The first year of Trump’s second term has likely left Vietnamese leaders simultaneously relieved by America’s focus on the Western Hemisphere and unsettled by its willingness to violate sovereignty and remove leaders it dislikes, creating the confusion that characterizes this strange partnership between former enemies who still can’t quite decide whether they’re friends.