Understanding America’s Economic Reality: A Conversation with Gary Cohn

The Tale of Two Economies

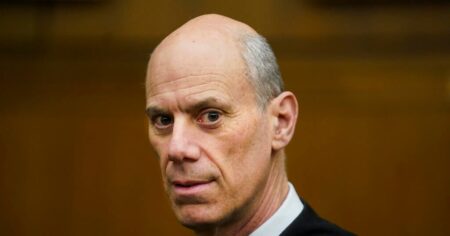

When Gary Cohn, IBM’s vice chairman and former top economic advisor to President Trump, sat down with Margaret Brennan on “Face the Nation,” he painted a picture of an American economy that tells two very different stories. On paper, the numbers look impressive – GDP growth is hovering around 5%, significantly higher than the baseline we’ve seen over the past decade. Inflation has cooled to the high 2% range, and unemployment remains relatively stable between 4-4.5%. These are the kinds of figures that would normally signal prosperity and economic health. Yet beneath these headline numbers lies a troubling reality that Cohn doesn’t shy away from addressing: while wealth accumulates at the top, ordinary working Americans are struggling to make ends meet. This disconnect between statistical success and lived experience has become the defining characteristic of our current economic moment, and it’s something the White House can no longer ignore as they look ahead to midterm elections.

The interview reveals a candid assessment from someone who understands both the corporate world and government policy-making. Cohn acknowledges that President Trump’s recent Wall Street Journal editorial claiming economic success stems from his tariff policies requires context and scrutiny. While the administration celebrates top-line growth, real families are facing genuine hardship when it comes to basic affordability – groceries, housing, healthcare, and everyday expenses that comprise the actual economy people experience. This is why, as Cohn explains, the president plans to spend significant time on the road talking specifically about affordability issues. It’s a tacit admission that despite rosy aggregate numbers, there’s a political and economic problem that needs addressing. The White House’s messaging strategy of telling people they’ll “just feel better after tax time” seems disconnected from the reality of households living paycheck to paycheck, watching their purchasing power erode even as economists tout growth figures.

The Corporate Layoff Wave Nobody Expected

One of the most striking contradictions Cohn addresses is the wave of corporate layoffs happening precisely when economic indicators suggest everything is going well. Just in the previous week before the interview, over 60,000 layoff announcements came from major American companies – Amazon cutting 16,000 corporate positions, MasterCard reducing its workforce by 4%, UPS eliminating 30,000 jobs, Dow shedding 4,500 positions, and Home Depot cutting 800. If the economy is truly thriving, why are so many people losing their jobs? Cohn offers a nuanced explanation that reveals much about how corporate America adapted to and is now adjusting from the COVID-19 pandemic’s disruptions.

According to Cohn, companies “hoarded labor” during and after the pandemic. When employees shifted to remote work, productivity declined, and corporations worried about meeting their workload demands. Rather than risk being short-staffed, they hired aggressively and avoided letting anyone go, causing workforces to balloon beyond what was truly necessary. Now, several years later, companies have become comfortable with their hiring and firing capabilities again. They understand the labor market better and feel confident they can find workers when needed. This has led to what Cohn describes as “rightsizing” – corporations trimming their headcount from pandemic-era bloat to more normalized levels. It’s a corporate efficiency move that makes sense on a spreadsheet but translates to real human cost for thousands of families suddenly without income.

But there’s another factor driving these layoffs that Cohn identifies: rising input costs. Companies are facing higher expenses across the board – increased labor costs, rising commodity prices, and yes, tariffs. Despite what the president claims about tariffs not hurting companies, Cohn points out the obvious mathematical reality: the administration boasts about having collected over $200 billion in tariff revenue, which means someone is paying that money, and it’s corporations. These businesses now find themselves in an impossible squeeze – their costs are rising significantly, but they can’t raise prices on consumers because, as Cohn acknowledges, Americans are already struggling to afford things. The result is that companies absorb what they can and cut what they must, which means layoffs. This creates a vicious cycle where job losses further reduce consumer spending power, potentially slowing the very economic growth the administration is celebrating.

The Credit Card Conundrum and Housing Market Reality

When the conversation turns to the White House’s proposed solutions for struggling consumers, Cohn’s expertise in financial markets comes to the fore, and his assessment is diplomatically critical. The administration has floated several ideas aimed at putting more money in people’s pockets: capping credit card interest rates at 10% for one year, limiting institutional investors from purchasing single-family homes, and potentially sending out $2,000 checks to Americans. While Cohn commends the White House for recognizing that people are “cash trapped” without sufficient disposable income, he’s blunt about the likely outcomes of these policies – they probably won’t solve the problem and might actually make things worse.

The credit card rate cap proposal particularly concerns him. Cohn explains that credit card companies charge interest based on risk – borrowers with worse credit histories and higher probabilities of defaulting pay higher rates. This isn’t arbitrary cruelty; it’s how lenders price the risk of not being repaid. If you impose a 10% cap on interest rates, what happens to people who currently carry cards with 20% or 25% rates because they’re higher-risk borrowers? The credit card companies won’t suddenly decide to lend to them at a loss. Instead, they’ll simply stop lending to the riskiest portion of the population altogether. Those consumers – often the very people the policy aims to help – will lose access to credit entirely, reducing rather than increasing their purchasing power. It’s a classic example of well-intentioned policy creating perverse outcomes, where helping people in theory hurts them in practice.

On the housing front, Cohn provides important historical context that challenges the current narrative about institutional investors. He reminds viewers that large-scale institutional buying of single-family homes didn’t happen arbitrarily or maliciously – it occurred after the 2008 financial crisis when the housing market collapsed. At that time, there was a massive glut of homes, prices were plummeting, and the market was in free fall. Financial institutions stepped in and purchased properties, effectively putting a floor under housing prices and preventing an even more catastrophic market collapse. While there are legitimate concerns about housing affordability today and the role of corporate landlords, Cohn cautions against forgetting how important these financial players can be during times of crisis. It’s a nuanced position that acknowledges current problems while warning against overcorrection that might create future vulnerabilities.

Kevin Warsh and the Future of the Federal Reserve

A significant portion of the interview focuses on President Trump’s nomination of Kevin Warsh to chair the Federal Reserve, and Cohn’s endorsement is both enthusiastic and substantive. Having worked closely with Warsh during the 2008 financial crisis – when Cohn was president of Goldman Sachs and Warsh was a Fed governor – he speaks from direct experience about Warsh’s capabilities during moments of extreme economic stress. Cohn credits Warsh as being “instrumental” during that crisis, serving as the point person at the Fed for all the bank mergers and asset transfers that helped stabilize the financial system. In Cohn’s assessment, without Warsh’s expertise and involvement, the United States would not have emerged from 2008 as successfully as it did.

Looking forward, Cohn anticipates that Warsh will return the Fed to what he calls “traditional norms,” focusing on core financial issues rather than expanding into broader social or political territory. On interest rate policy, where there’s currently pressure for cuts, Cohn expects Warsh to implement perhaps one or two rate reductions during the year. More significantly, he predicts Warsh will work to reduce the Fed’s balance sheet, which ballooned during quantitative easing programs when the central bank purchased enormous amounts of securities. Warsh has historically opposed maintaining such a large balance sheet, and Cohn expects him to pursue a gradual sell-down of those holdings, effectively reversing years of monetary expansion.

On the regulatory front, Cohn describes Warsh as a “traditionalist” who believes in strong regulation but regulation that actually works – that protects the financial system while still allowing markets to grow and consumers to access capital. When Warsh’s nomination was announced, the markets responded immediately and positively, which Cohn takes as validation. The dollar strengthened by about 1%, while precious metals like silver and gold dropped by 25% and 10% respectively. These movements suggest market confidence in Warsh’s approach and anticipated policies. The interview takes a lighter turn when Brennan mentions Trump’s joking threat to “sue Warsh” if he doesn’t lower interest rates, which Cohn dismisses as humor while affirming that both the president and Warsh understand and respect the Fed’s independence – a crucial principle for maintaining credibility in monetary policy.

The Political Reality Behind Economic Messaging

What emerges clearly from this conversation is the gap between economic statistics and political reality. The White House finds itself in the awkward position of wanting to claim credit for strong GDP growth and improved inflation while simultaneously acknowledging that many Americans are suffering financially. This is why, as Cohn notes, “affordability is going to be the issue” between now and the midterm elections. The administration’s strategy of having the president “go on the offensive” and spend time on the road discussing economic concerns is an implicit recognition that simply pointing to positive aggregate numbers isn’t politically sustainable when kitchen table economics tell a different story.

The challenge for any administration is that macroeconomic success and household financial security don’t always align, especially in an era of growing inequality. You can have robust GDP growth driven by productivity gains and corporate profits while wages stagnate and costs for essentials rise. You can have low unemployment while underemployment and job quality decline. You can have controlled inflation by traditional measures while housing, healthcare, and education costs spiral beyond reach for many families. Cohn’s analysis, drawing from his experience in both government and corporate leadership, illuminates these tensions without offering easy solutions, because there aren’t any.

Understanding Economic Complexity in Polarized Times

Perhaps the most valuable aspect of this interview is Cohn’s willingness to acknowledge complexity and trade-offs rather than retreating into partisan talking points. He credits the administration with strong topline numbers while pointing out that policy proposals like credit card rate caps might backfire. He explains corporate layoffs as partially rational adjustment rather than pure greed while acknowledging the real pain they cause. He defends institutional investors’ role in housing market stabilization while not dismissing affordability concerns. He enthusiastically supports Warsh’s Fed nomination while maintaining that the central bank must remain independent from presidential pressure.

This kind of nuanced economic analysis is increasingly rare in our polarized political environment, where complex realities are often flattened into simplistic narratives that serve partisan purposes. The economy is neither the unambiguous success the administration claims nor the complete disaster opposition voices might suggest. It’s a mixed picture where aggregate strength coexists with individual struggle, where policy interventions create both intended and unintended consequences, and where solutions to one problem often create or exacerbate others. As we move toward midterm elections with economic policy at the center of political debate, the kind of clear-eyed assessment Cohn provides – acknowledging both achievements and challenges, recognizing both market signals and human costs – offers a model for how we might discuss these issues more productively, even if that nuance doesn’t always translate well into campaign slogans or cable news soundbites.